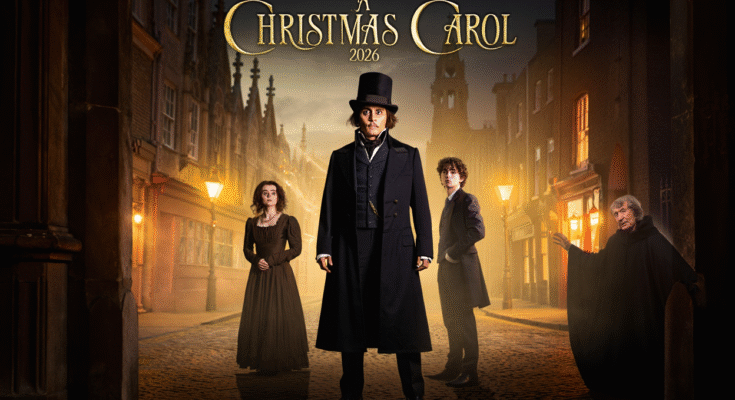

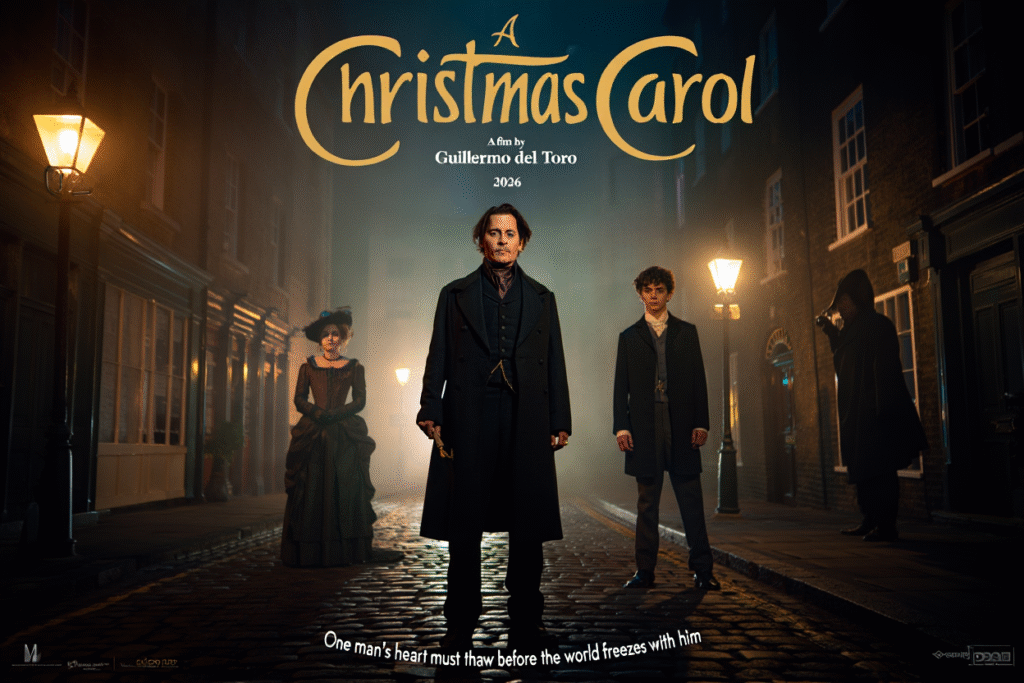

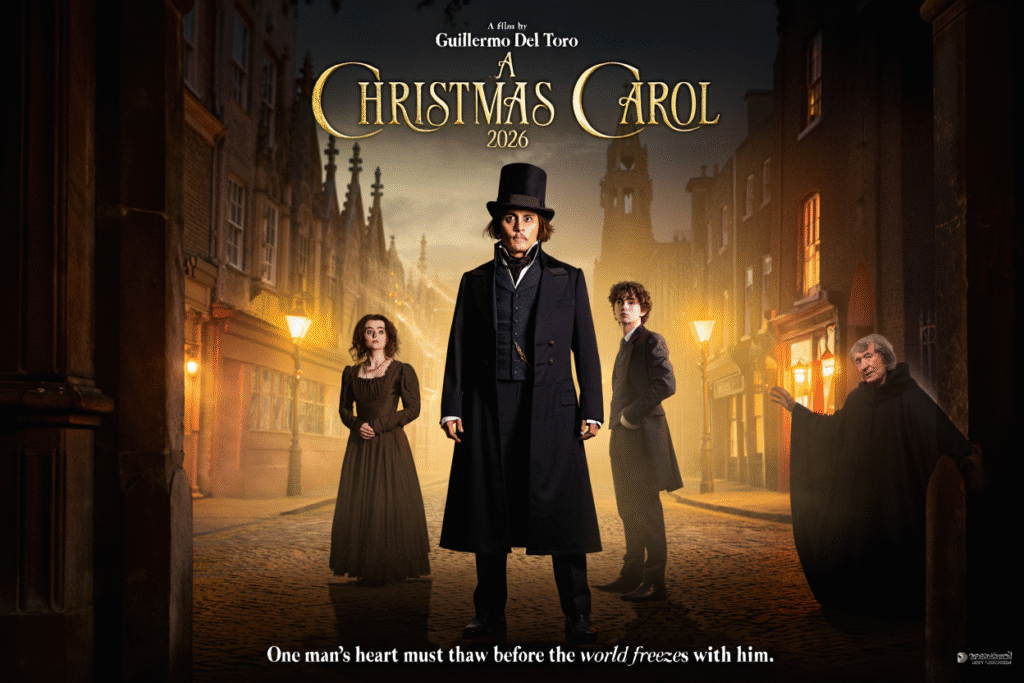

When Guillermo del Toro steps into a story, he doesn’t just retell it — he resurrects it. A Christmas Carol (2026) is not merely another adaptation of Dickens’ immortal tale; it is a haunting hymn to memory, loss, and the fragile possibility of change. In del Toro’s hands, Victorian London becomes a living organism — part dream, part nightmare — and within its frostbitten veins beats the heart of a man learning, too late and just in time, to feel again.

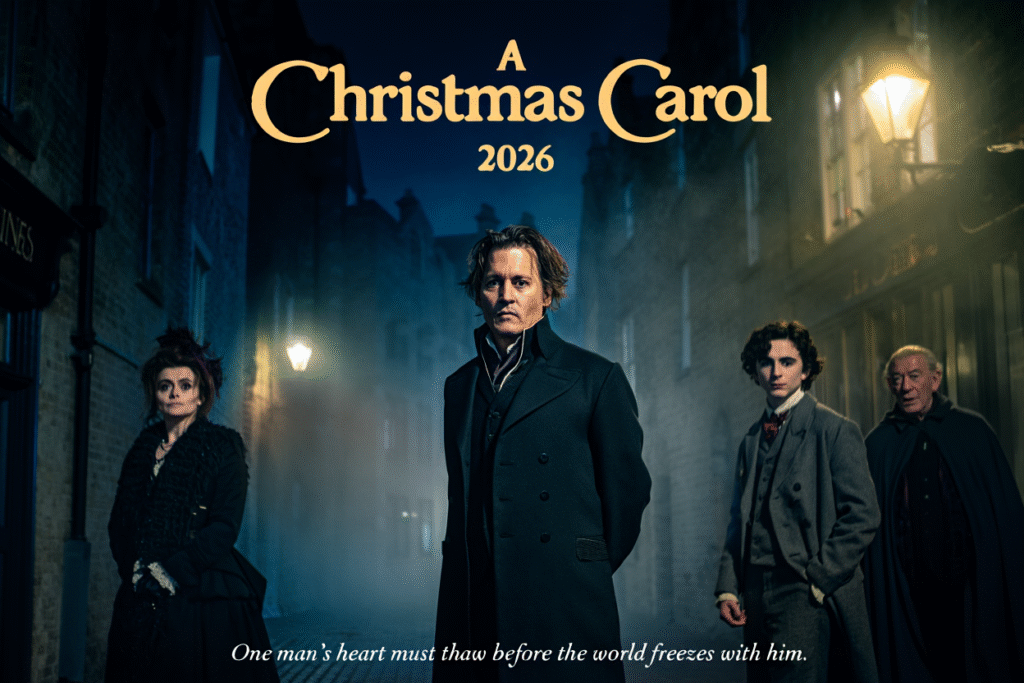

Johnny Depp’s Ebenezer Scrooge is not the sneering miser of past tellings. He is a man eroded by grief — a reclusive clockmaker whose life has become a museum of time stopped. Surrounded by the relentless ticking of his creations, he is a prisoner of minutes, each tick a reminder of the one moment he failed to hold onto. Depp gives one of his most layered performances in years, portraying Scrooge as both a phantom and a man of flesh, a ghost who doesn’t yet realize he’s still alive.

From the film’s first frame, del Toro’s signature aesthetic reigns supreme. London isn’t just gloomy — it breathes. Gas lamps flicker like dying stars; snow drifts through narrow alleys like whispered prayers. Every shot is composed with painterly precision, the blend of live action and stop-motion creating an uncanny realism where candlelight and shadow dance as if alive. The result is an atmosphere both claustrophobic and transcendent, where even despair looks beautiful.

The arrival of Jacob Marley (Ian McKellen) sets the tone for everything that follows. McKellen’s voice, rich and trembling, gives Marley a tragic dignity — less a monster than a mourner. His spectral chains shimmer with memory, each link forged not only by greed but by love unfulfilled. When he warns Scrooge that time is almost up, it feels less like condemnation than compassion — a ghost begging another soul not to share his fate.

Then come the three spirits, each rendered with exquisite imagination. Helena Bonham Carter’s Ghost of Christmas Past glows like candle wax in the dark, her ethereal presence both soothing and unsettling. She drifts through Scrooge’s memories as if wading through water, her every word rippling with nostalgia. Timothée Chalamet’s Ghost of Christmas Present is a revelation — youthful, radiant, yet burdened. His laughter hides exhaustion, his warmth conceals a growing sorrow at humanity’s blindness. Together, they weave a spell that is part lullaby, part requiem.

Del Toro’s filmmaking transforms these encounters into operatic vignettes. The past unfolds in sepia tones that bleed into color; the present bursts with candlelight and music; the future collapses into silence and snow. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a towering marvel of design — a living silhouette whose movement bends the world around it. Its presence freezes not just Scrooge, but the audience, in awe.

What distinguishes this Christmas Carol from its countless predecessors is its willingness to dwell in pain. Redemption here is not a switch flipped by magic, but a process of breaking — the slow, reluctant surrender of a man who has forgotten what it means to need. Depp’s face tells that story wordlessly; every tremor, every breath is an unmasking. His final transformation feels earned because it hurts.

The supporting cast amplifies the tragedy and tenderness. Bonham Carter’s wistful charm, Chalamet’s fragile joy, and McKellen’s mournful gravity orbit around Depp like celestial bodies drawn to a dying sun. Each represents a fragment of Scrooge’s soul, each demanding that he confront what he has lost. Del Toro gives them moments of quiet poetry — a touch, a glance, a ghostly tear that falls upward instead of down.

Visually, the film is a feast of contrasts — decay and splendor intertwined. Del Toro fills his frames with textures: cracked porcelain angels, clock gears rusted with regret, candle flames trembling in the breath of unseen spirits. His London is both a graveyard and a cradle. Through it all, composer Alexandre Desplat’s score drifts like a hymn from another world — delicate piano notes rising against choirs that sound half-human, half-angelic.

And then there’s the ending — simple, radiant, devastating. As Scrooge steps into the snow, reaching out to the boy with the goose, time itself seems to pause. Depp’s voice trembles as he whispers “Merry Christmas,” not as a greeting but as a confession. In that instant, del Toro captures the essence of Dickens’ message: that love, once found, is enough to thaw the longest winter.

A Christmas Carol (2026) is not merely a retelling — it is a resurrection of the soul. Del Toro turns the familiar fable into a darkly luminous meditation on regret and grace, anchored by one of Johnny Depp’s finest performances. It’s a film of ghosts and gears, of sorrow and salvation, and when the final snowflake falls, you realize it’s not just Scrooge who has been saved. It’s us.