There are horror films that make you jump — and then there are horror films that haunt your thoughts long after the credits fade. The Unborn Curse (2025) belongs firmly in the latter category: a nightmarish, slow-burning descent into spiritual dread and psychological collapse. Directed with terrifying elegance and anchored by two powerhouse performances, it is not merely a story about possession or the occult — it’s a story about how love, when twisted by desperation, can become the most unholy ritual of all.

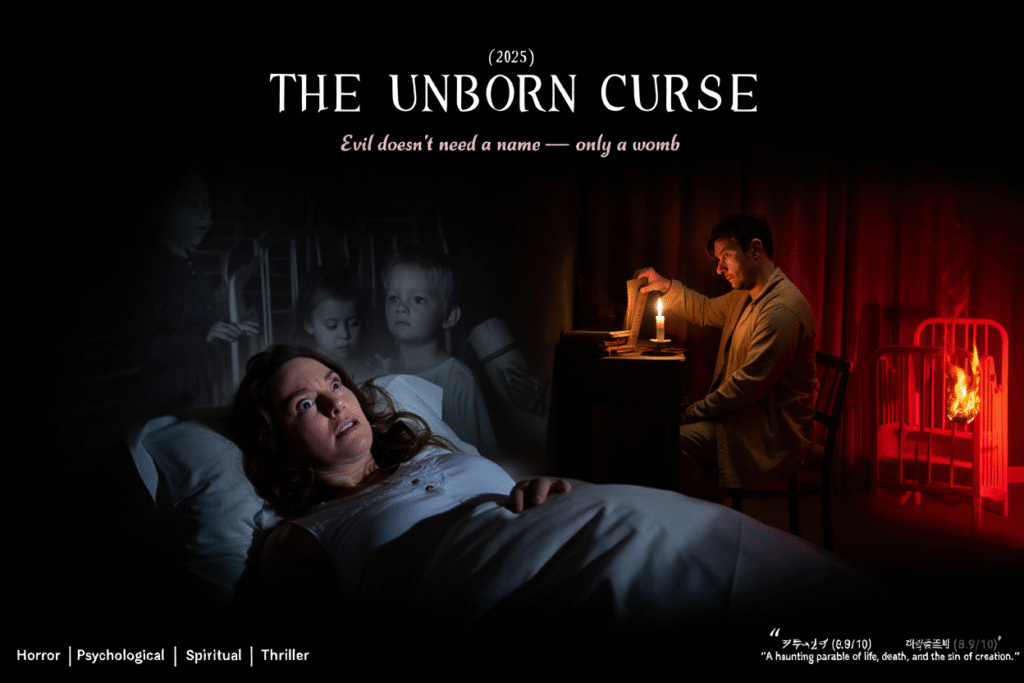

The film opens with silence — the kind that feels like a held breath. Claire and David Halloway (played with aching authenticity by Florence Pugh and Oscar Isaac) are a married couple living in the gray shadow of infertility. Their home, once filled with laughter, now feels more like a shrine to failure. After a final failed IVF attempt, Claire collapses in prayer, her whispered plea echoing through the dark like a bargain struck with unseen forces. When she miraculously conceives soon after, joy floods back into their lives — but something in the air feels off, as though the light that found them came from the wrong source.

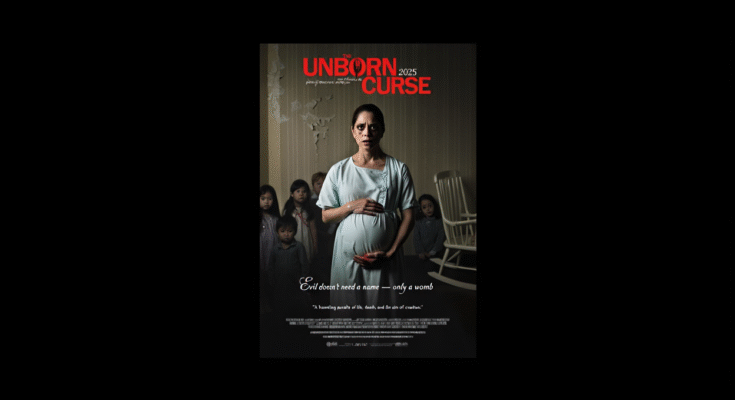

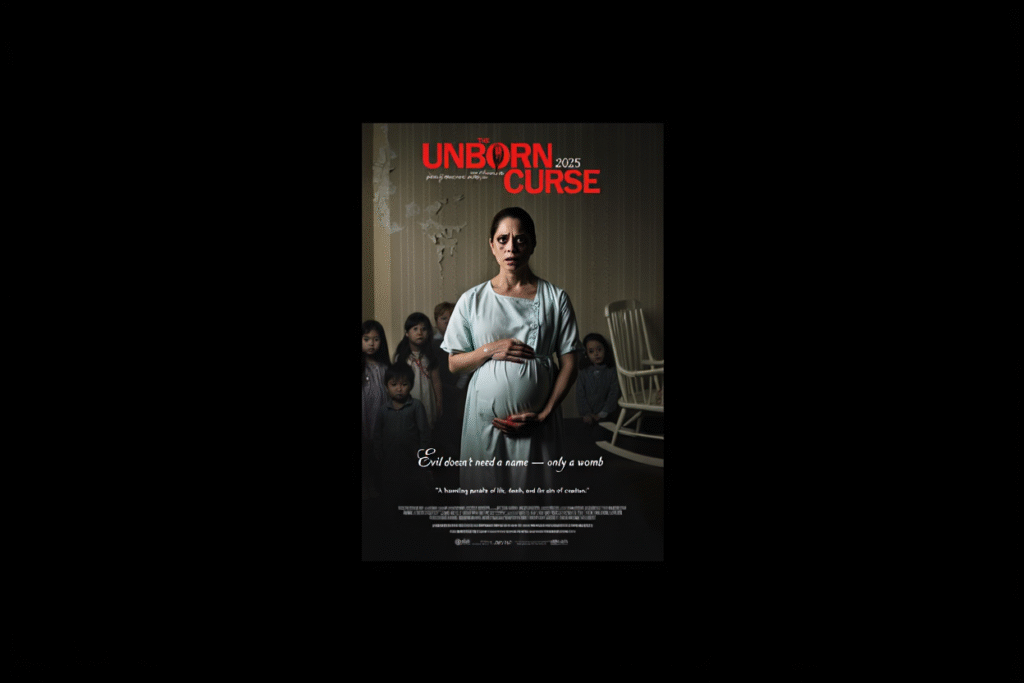

From the first trimester, director Jennifer Kent (The Babadook) crafts unease through suggestion rather than spectacle. The nursery lights flicker, the baby monitor whispers static that shapes into syllables, and mirrors warp just slightly when Claire passes by. The pregnancy, once celebrated, turns harrowing as she begins to see things that shouldn’t exist — children with hollow eyes, umbilical cords trailing like nooses, and a charred crib that reappears no matter how many times it’s burned. Pugh’s performance is nothing short of extraordinary: fragile, feral, and utterly believable as a woman caught between motherhood and madness.

Meanwhile, David’s arc deepens the film’s tragedy. His love becomes investigation — sleepless nights spent digging through church records and old manuscripts to uncover the truth behind the mysterious midwife who “helped” them conceive. What he finds is horrifying: a centuries-old covenant, forged during a famine, in which barren couples offered their unborn to a spirit called The Nameless. It was said that the child would live — but only if the parents’ souls were pledged in return. As David reads aloud the ancient contract, the film’s score, an atonal heartbeat by composer Colin Stetson, throbs like a pulse from another world.

Kent’s direction is a masterclass in restraint and revelation. The horror doesn’t come from cheap shocks, but from the creeping sense that the characters are being erased piece by piece. Every ultrasound becomes a séance. Every prayer turns into a plea. The unborn child grows, but so does something else — something that feeds on faith, twisting love into hunger. By the time Claire begins to speak to her stomach in a voice that isn’t quite her own, the film has fully crossed into psychological terror of the highest order.

Visually, The Unborn Curse is a work of art drenched in nightmare. Cinematographer Greig Fraser paints every frame in muted gold and shadow, making domestic spaces look like cathedrals of decay. Religious imagery pervades the film — crucifixes that bleed, rosaries that turn to ash, candles that won’t stay lit. Yet beneath the horror lies something more human: a story about grief, guilt, and the price of wanting too much.

As the due date nears, time fractures. The film’s final act unfolds like a fever dream — the walls of the house pulsing with life, Claire’s belly glowing from within as if lit by fire. When labor begins, the world itself seems to convulse. The delivery scene — part exorcism, part birth, part cosmic punishment — is one of the most harrowing sequences in modern horror. Without spoiling the ending, Kent ensures that the final image burns itself into your mind: a cradle rocking in an empty room, and a voice whispering, “Thank you for believing.”

What makes The Unborn Curse transcend its genre is its refusal to explain everything. It is a film of faith and fear in equal measure — a spiritual horror for an age where miracles feel transactional and divinity feels absent. The true terror lies not in the creature that may be born, but in the realization that it was invited.

Florence Pugh and Oscar Isaac elevate the script beyond the supernatural. Their chemistry — both tender and tormented — anchors the film’s abstract terror in emotional truth. Their love story, corrupted by yearning, becomes the real monster. The horror is not that evil found them, but that they sought it out with open arms.

In the end, The Unborn Curse (2025) lingers like a prayer left unanswered — beautiful, broken, and utterly devastating. It asks a question too terrifying to face and too human to ignore: what if creation itself is a sin when born from despair?