There’s a moment, early in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: Reborn, where the camera just stares — unblinking — at an empty field. The air hums. Cicadas scream. The light trembles as if the sun itself is complicit. Then, somewhere in that stillness, a sound emerges — the dry, guttural cough of a chainsaw sputtering to life. It’s not nostalgia. It’s a warning. And with that, the nightmare begins again.

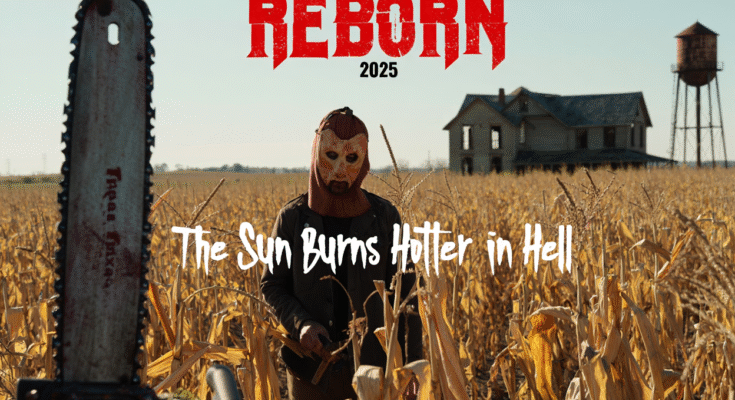

Set in a decayed stretch of rural Texas that feels forgotten by both God and Google Maps, Reborn resurrects Tobe Hooper’s 1974 masterpiece with reverence and venom. Gone are the neon gloss and self-aware irony that have haunted modern horror. In their place: dust, sweat, bone, and madness. This is not a sequel — it’s a resurrection. A fever dream of heat and horror where daylight is more terrifying than darkness.

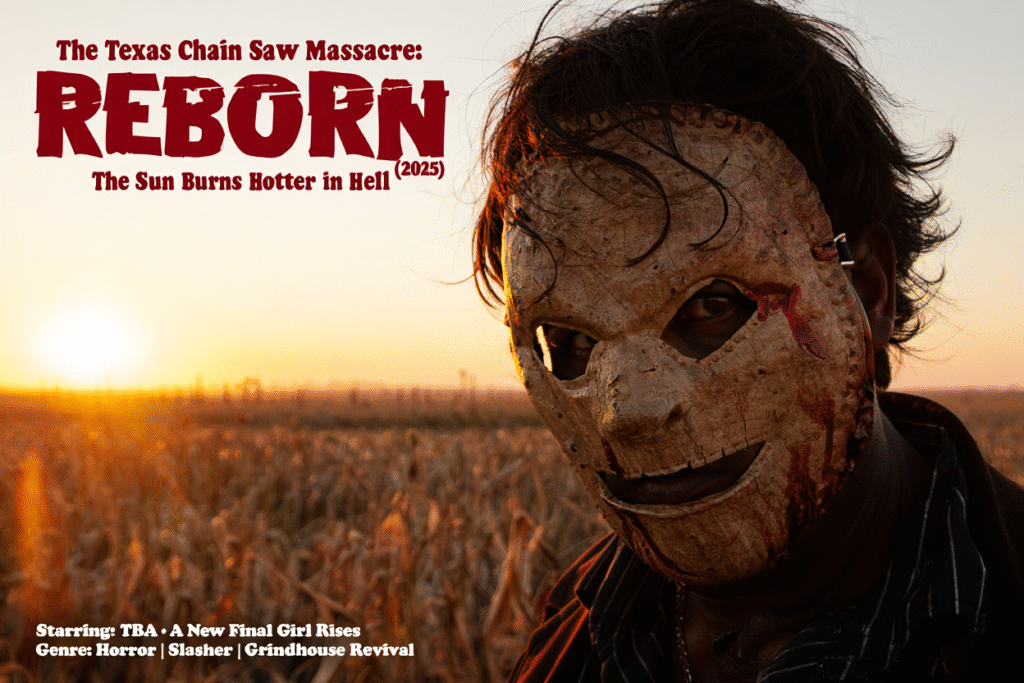

The film’s anonymous creative team (TBA, for now) leans hard into grindhouse realism. Every frame looks like it was left too long in the sun — grainy, brittle, and bleeding at the edges. There’s no score in the opening twenty minutes, just wind, flies, and the throb of something distant. When Leatherface finally emerges, it’s almost too much. He’s not presented as a monster, but as an inevitability — the product of a world that’s been rotting for decades.

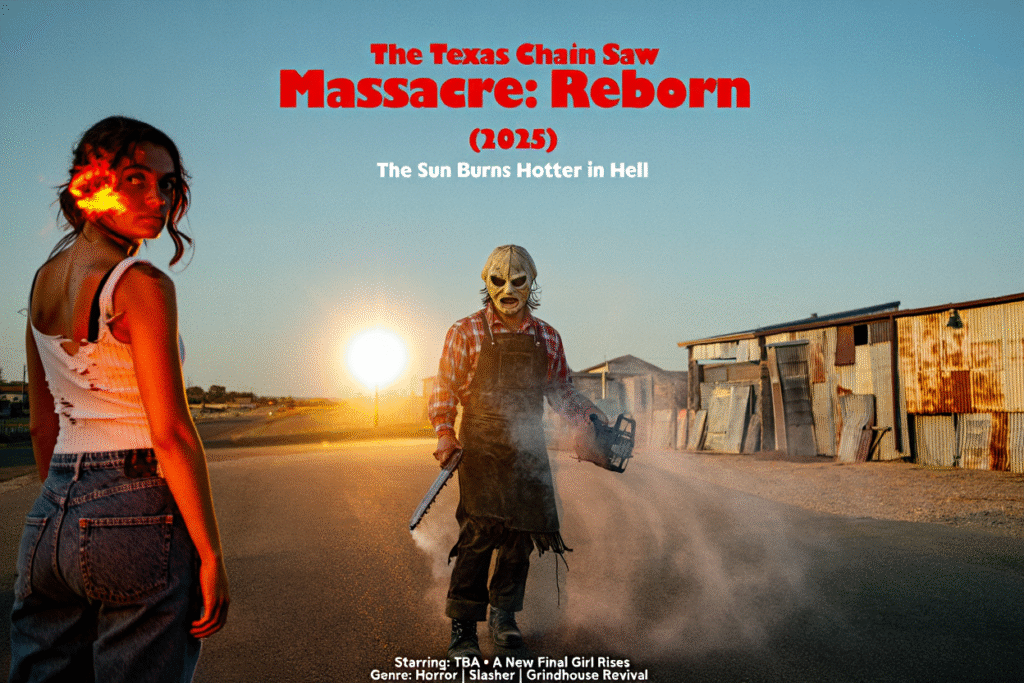

And yet, the film’s soul doesn’t belong to him. It belongs to her — the new Final Girl. She’s nameless for most of the film, a drifter whose truck breaks down on the wrong backroad. But what sets her apart isn’t innocence or luck — it’s ferocity. She doesn’t scream when the chainsaw revs. She studies it. Learns its rhythm. Adapts. Her survival tactics are born from raw improvisation: she welds road flares into torches, zip ties into armor, and uses a cattle gate as both weapon and barricade. By the final act, she’s not running from the monster — she’s rewriting the map of his home.

The film’s middle stretch is a sensory assault. Long, hypnotic takes of heat haze and decay replace the jump scares. A slaughterhouse-turned-storage maze becomes the stage for one of the most claustrophobic chases in modern horror — lit entirely by flare light and trembling breath. The editing fractures time, creating a rhythm that feels like panic itself: too fast to process, too slow to escape.

Leatherface, as reimagined here, is almost mythic. His presence is built through absence — the twitch of a chain, the sound of boots scraping concrete, the faint echo of laughter that could just be wind. When he finally steps into frame, it’s in full sunlight, apron stiff with old blood, saw glinting like scripture. The terror isn’t that he’s returned — it’s that he never left.

Visually, Reborn is a masterclass in degradation. The cinematography turns the Texas landscape into a hallucination — blinding whites, scorched yellows, and blacks that swallow the horizon. Every shot feels diseased. Every object, from a butcher’s hook to a watermelon stand, hums with implied violence. The camera doesn’t look at horror; it inhabits it. It’s what Hooper might have done with today’s tools — or what today’s tools might do if left in his hands too long.

Beneath the grime and gore, though, beats a strange, almost spiritual undercurrent. The film’s tagline — “The Sun Burns Hotter in Hell” — isn’t just a threat. It’s a philosophy. This is a world where faith has been stripped for parts, where survival has replaced salvation. The final girl’s transformation feels less like triumph and more like transcendence — she doesn’t defeat evil; she joins the ritual of endurance. The closing scene, silent but scorching, feels biblical in its simplicity: blood, fire, and one woman walking away into a horizon that looks exactly like the mouth of Hell.

For longtime fans, Reborn feels like a cleansing fire — a brutal, sun-scorched reminder of what made The Texas Chain Saw Massacre matter. It’s not about kills, or mythology, or even Leatherface himself. It’s about the moment when fear becomes faith — when the scream turns into survival. This isn’t horror for comfort. It’s horror as confrontation.

If 1974’s Massacre was a shriek of rebellion, Reborn is its echo, older but just as furious. It understands that real terror doesn’t come from darkness — it comes from exposure. The light is merciless. The heat doesn’t forgive. And somewhere in that blinding, buzzing inferno, Leatherface waits, patient as ever, sharpening the blade that time could never dull.