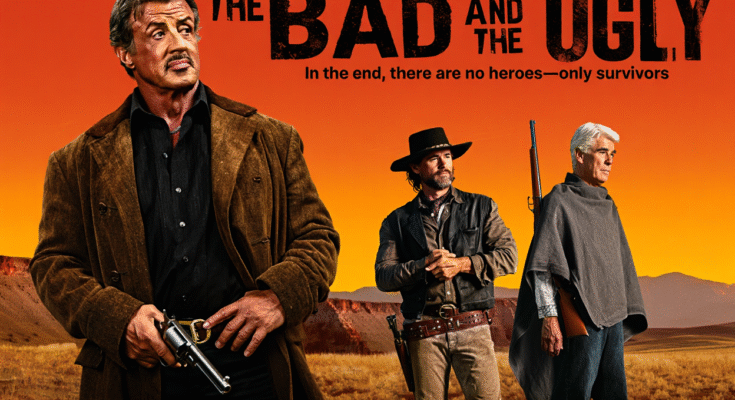

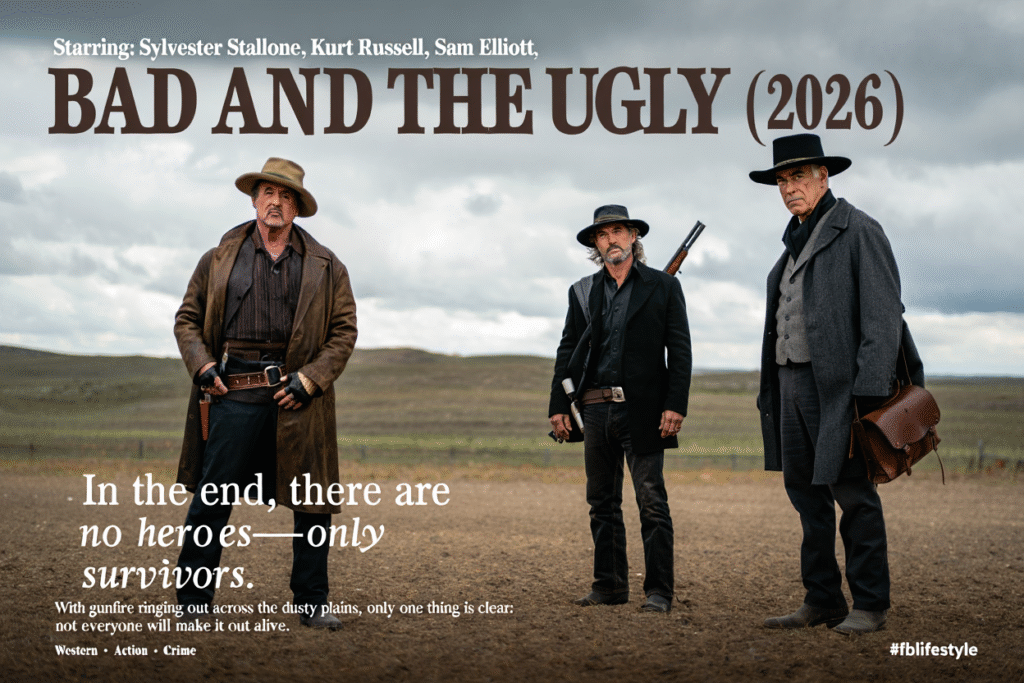

Bad and the Ugly (2026) rides into the modern Western landscape with the weight of legend on its shoulders and the grit to earn its place there. This is not a nostalgic tribute or a romanticized vision of the frontier—it’s a hard-edged, blood-stained reimagining where age, regret, and violence collide under a merciless sun. From its opening moments, the film makes one thing clear: this world does not reward goodness, only endurance.

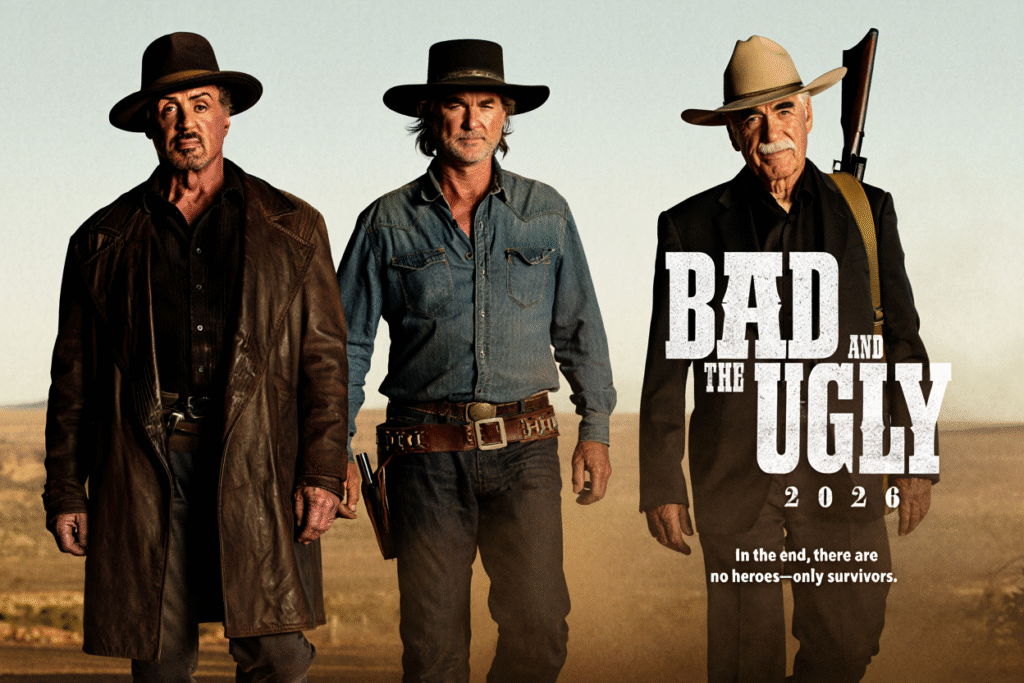

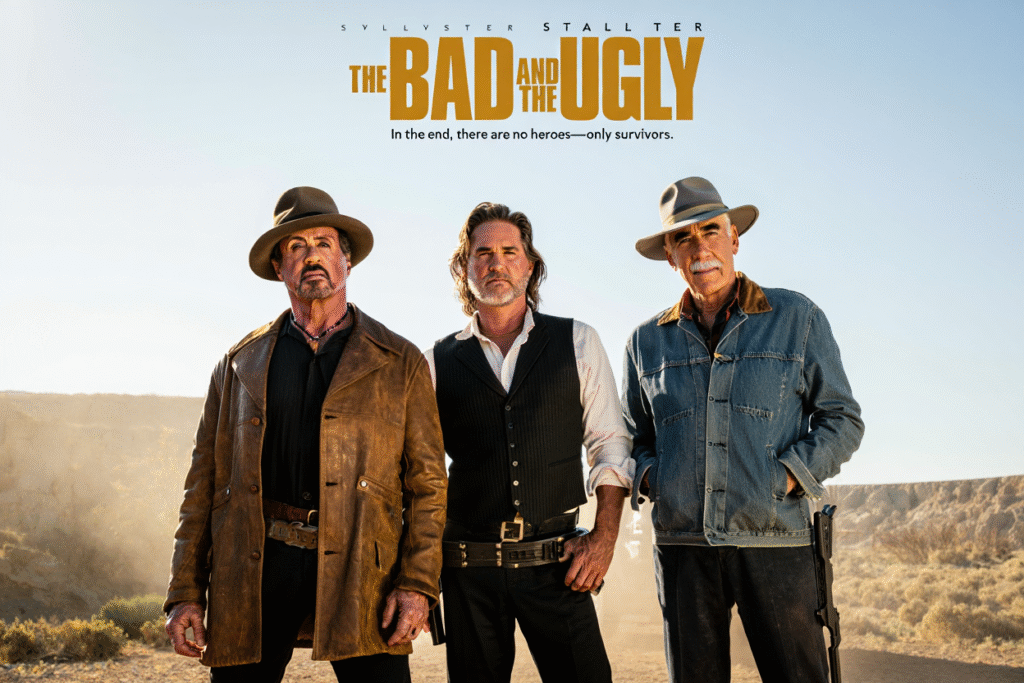

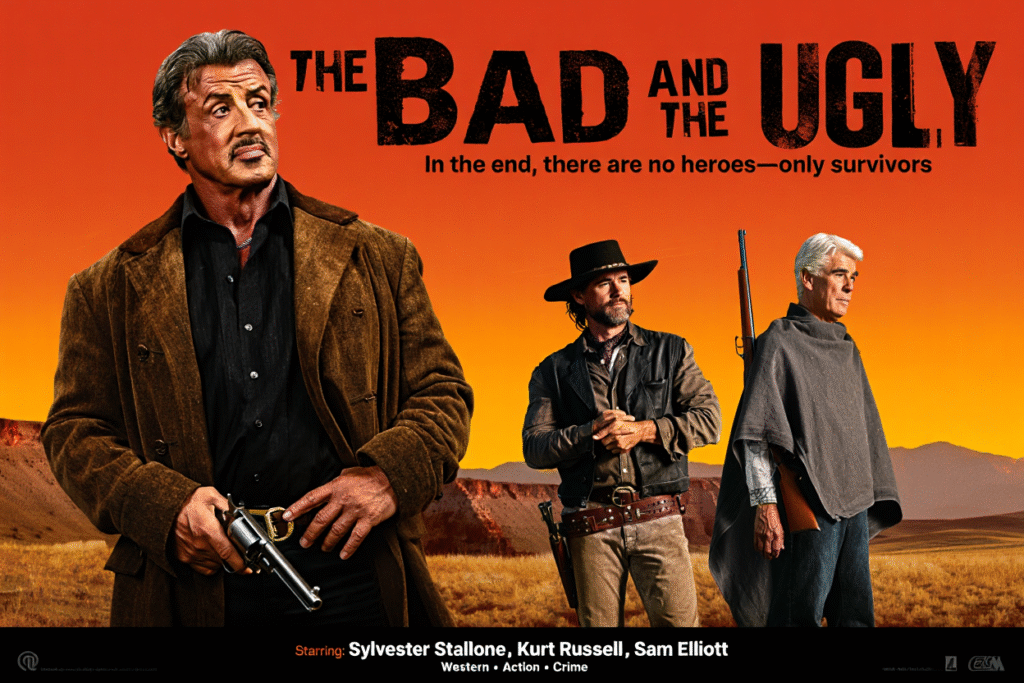

Sylvester Stallone delivers a raw, weathered performance as the brutal enforcer searching for redemption in a land that has long since stopped believing in it. His presence is heavy, deliberate, and quietly tragic. Every scar on his face feels earned, every word spoken like it costs him something. Stallone doesn’t play a hero—he plays a man trying to outlive the worst version of himself.

Kurt Russell, effortlessly magnetic, embodies the sly outlaw driven by revenge rather than survival. His character is charming, dangerous, and unpredictable, masking pain behind wit and menace. Russell understands restraint, letting silence and subtle expressions do the work, creating a character who feels both seductive and deeply untrustworthy. You never fully know which side of him you’re going to meet—and that tension fuels the film.

Sam Elliott is the soul of Bad and the Ugly. As the aging lawman chasing one last score, he brings gravitas, melancholy, and a quiet wisdom shaped by decades of regret. His voice alone carries the weight of lost ideals, and his performance anchors the film emotionally. Elliott doesn’t chase justice—he chases closure, and that distinction makes all the difference.

The dynamic between the three men is the film’s beating heart. Their alliance is fragile, transactional, and doomed from the start. Every shared glance feels like a calculation, every moment of cooperation tinged with the certainty of betrayal. The screenplay thrives on this tension, allowing mistrust to simmer rather than explode prematurely.

Visually, the film is stunning in its brutality. The dusty plains, scorched horizons, and decaying towns are shot with an unforgiving eye, stripping the West of any romantic glow. Blood blends with dirt, and gunfights are chaotic, loud, and frighteningly fast—less choreography, more consequence. Violence here is never stylish; it’s necessary, ugly, and final.

The action sequences are sparse but impactful, each one carrying narrative weight. When bullets fly, they do so with purpose, changing the balance of power and the emotional direction of the story. The film understands that restraint makes violence more powerful—and more unsettling.

Thematically, Bad and the Ugly dismantles the idea of heroism. It questions whether redemption is earned through good deeds or simply surviving long enough to regret what you’ve done. In this world, morality is a luxury the dead can afford, not the living. The film never judges its characters—it simply watches them unravel.

What elevates the story is its willingness to let its characters fail. No one is clean. No one is fully right. Every decision costs something, and the film allows those costs to linger. This emotional honesty gives the story a tragic inevitability that feels both classical and painfully modern.

The score underscores this tone perfectly—minimalist, haunting, and slow-burning. Rather than guiding emotions, it shadows them, reinforcing the sense that fate is already sealed long before the final showdown begins.

In the end, Bad and the Ugly (2026) is a Western stripped to its bones: survival over honor, instinct over justice, and truth revealed only when it’s far too late. It’s not a film about heroes—it’s about what’s left when heroism dies. Gritty, unapologetic, and powerfully acted, this is a Western that doesn’t ask for forgiveness… it dares you to endure it. ⭐⭐⭐⭐½