Lilith (2026) is not merely a dark fantasy—it is a cinematic elegy for the forgotten, the condemned, and the misunderstood. From its opening moments, the film announces itself as something operatic and emotionally ambitious, weaving gothic horror with tragic romance in a way that feels both ancient and painfully modern.

Charlize Theron delivers a commanding, near-mythic performance as Lilith. She is wrath incarnate, yet never hollow. Every glance carries centuries of exile, every movement feels burdened by divine injustice. Theron plays Lilith not as a monster, but as a woman shaped into one by betrayal, making her vengeance feel disturbingly justified.

The film’s greatest strength lies in how it treats Lilith’s rage as sacred rather than sensational. Her anger is not chaotic destruction—it is memory made flesh. The script allows her fury to coexist with longing, grief, and a desperate hunger to be seen not as a curse, but as a creator erased from history.

Tom Hiddleston’s Elias serves as the audience’s fragile bridge into Lilith’s world. As a mortal scholar obsessed with forbidden texts, he embodies curiosity as both salvation and sin. Hiddleston brings quiet melancholy to the role, portraying a man drawn not just to Lilith’s power, but to the loneliness beneath it.

The chemistry between Theron and Hiddleston is slow-burning and devastating. Their relationship unfolds like a doomed poem—measured, intimate, and inevitably tragic. Love here is not redemption guaranteed; it is risk, vulnerability, and the willingness to be destroyed by truth.

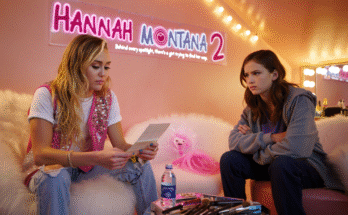

Anya Taylor-Joy’s Seraphine is a revelation. Rather than a simple antagonist, she is portrayed as a believer fractured by doubt. Her devotion to divine order clashes violently with her growing realization that righteousness may itself be corrupted. Taylor-Joy gives Seraphine an icy resolve that gradually cracks, revealing terror, envy, and buried compassion.

Visually, Lilith is breathtaking. Gothic cathedrals loom like judgment made stone, while shadow-soaked landscapes feel carved out of forgotten scripture. Fire, ash, and celestial light are used symbolically, reinforcing the film’s obsession with creation, destruction, and rebirth.

The score swells with mournful intensity, elevating the film’s mythic tone without overpowering its quieter moments. Silence is used just as effectively, allowing grief and desire to linger uncomfortably long, forcing the audience to sit with the weight of eternity.

What sets Lilith apart from other dark fantasies is its refusal to offer easy answers. Heaven is not purely good. Hell is not purely evil. The film interrogates free will, obedience, and the cruelty of cosmic hierarchies, asking whether rebellion is sin—or survival.

As the prophecy of the Mother of Shadows unfolds, the narrative tightens into a haunting meditation on choice. Each character must decide what they are willing to sacrifice: faith, love, identity, or the world itself. The final act is emotionally brutal, trading spectacle for consequence.

By the time Lilith (2026) reaches its conclusion, it leaves behind more than awe—it leaves scars. This is a film that lingers, refusing to be forgotten, much like its tragic heroine. Dark, romantic, and philosophically rich, Lilith is not just a story of vengeance—it is a requiem for a woman who dared to exist on her own terms.