Phasmophobia (2026) is not a horror film that screams for attention—it whispers, patiently, until the silence becomes unbearable. Rated a deserved five stars, this chilling psychological descent understands that true terror is not found in monsters lurking in the dark, but in the quiet certainty that something inside you is already awake.

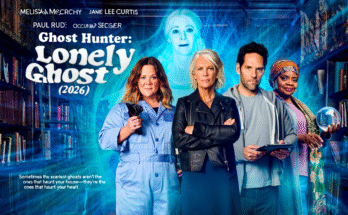

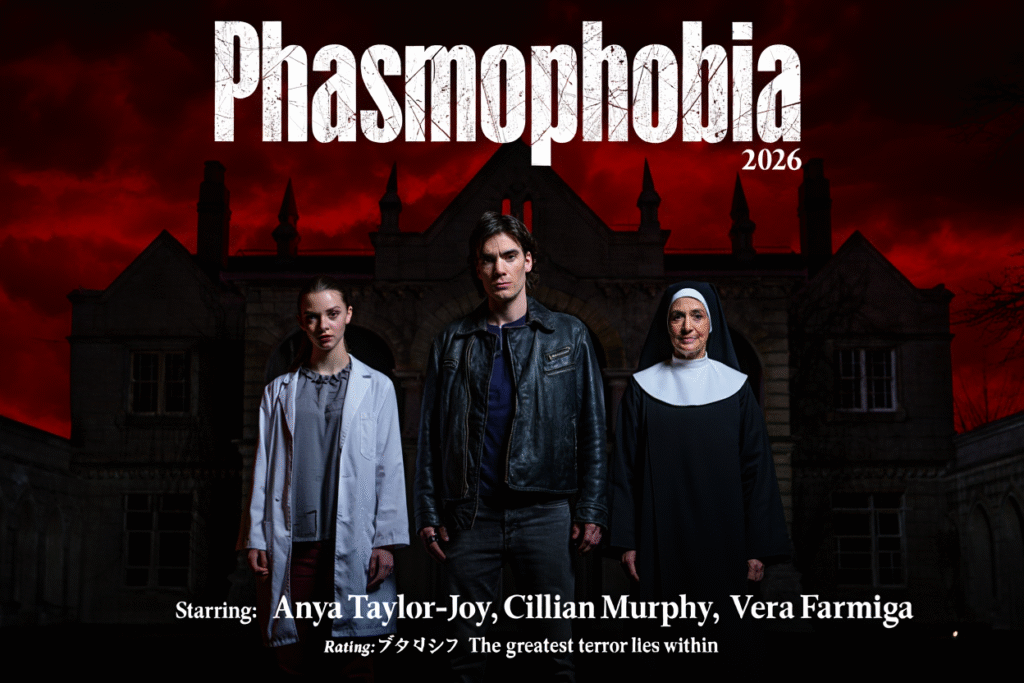

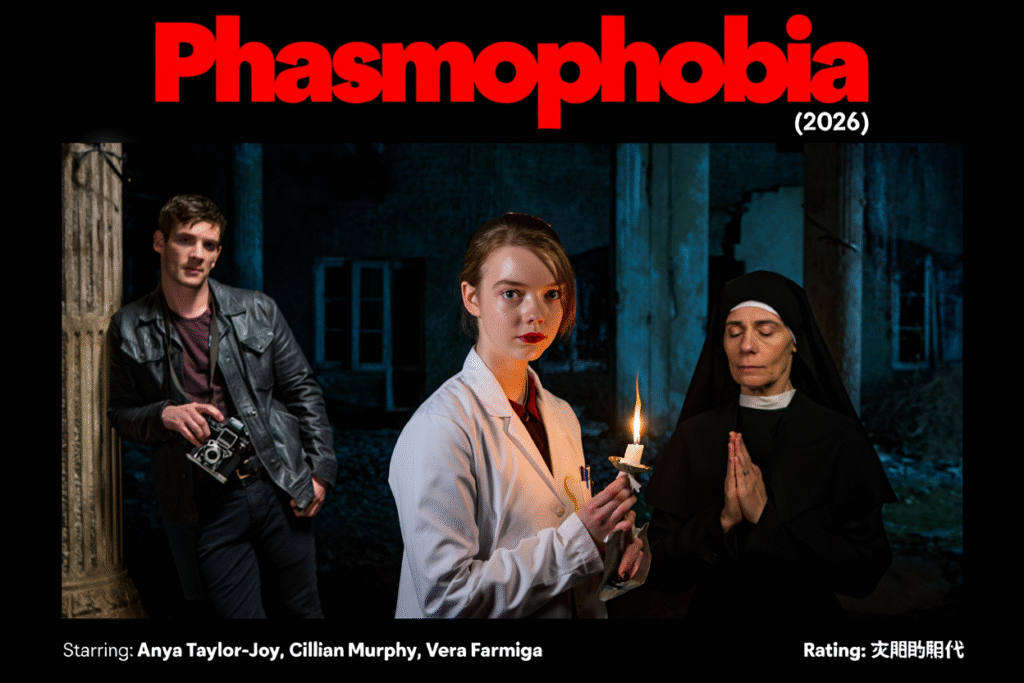

Anya Taylor-Joy delivers one of her most unsettling performances as Dr. Eleanor Voss, a clinical psychologist whose confidence in logic becomes her greatest vulnerability. From the moment she steps into the forgotten mansion, the film positions her not as a heroine, but as a subject—someone being studied, tested, and slowly unraveled by forces that understand her better than she understands herself.

Cillian Murphy’s Owen Hale serves as the perfect counterweight: skeptical, emotionally guarded, and armed with sarcasm as a defense mechanism. Murphy plays disbelief not as arrogance, but as fear in denial, making his gradual psychological erosion deeply compelling. Watching his certainty fracture is one of the film’s most quietly devastating arcs.

Vera Farmiga’s Sister Miriam is the film’s haunted soul, a woman who believes not because she wants to, but because she has already paid the price of knowing. Farmiga brings weary gravity to the role, grounding the supernatural elements with spiritual pain that feels lived-in and raw. Every glance suggests a history she wishes she could forget.

The mansion itself is the film’s true antagonist. It does not chase, attack, or announce itself. Instead, it listens. It adapts. The house manifests fear with surgical precision, crafting personalized nightmares that feel intimate rather than spectacular. Doors don’t slam for shock—they wait until you’re no longer sure they were ever closed.

Directorally, Phasmophobia excels in restraint. The film favors slow camera movements, suffocating stillness, and negative space, allowing the audience’s imagination to become complicit in the horror. When scares arrive, they feel earned, invasive, and deeply uncomfortable rather than theatrical.

What elevates the film beyond genre expectations is its psychological thesis: fear is not merely an emotion, but a language. The mansion doesn’t punish its victims—it communicates with them, forcing each character to confront the lies they’ve built their lives upon. Terror becomes a form of truth-telling.

Anya Taylor-Joy’s performance crescendos as Eleanor realizes that her professional detachment has been a way to outrun her own trauma. Her fear is not of ghosts, but of memory—of acknowledging that control was always an illusion. The horror peaks not with violence, but with recognition.

The film’s sound design deserves special praise. Breathing, whispers, distant echoes, and sudden absences of sound work together to destabilize the viewer’s sense of safety. Silence becomes louder than any scream, and once the film trains you to fear quiet moments, there is no escape.

Rather than offering neat resolutions, Phasmophobia chooses ambiguity. It respects the intelligence of its audience, leaving questions unanswered and wounds unhealed. The ending lingers not because of what it shows, but because of what it refuses to explain.

In the end, Phasmophobia (2026) is a rare horror film that doesn’t ask what scares you—it tells you. Intelligent, suffocating, and emotionally ruthless, it reminds us that the most terrifying haunted houses are not abandoned buildings, but minds that have learned to fear themselves. 👁️🖤