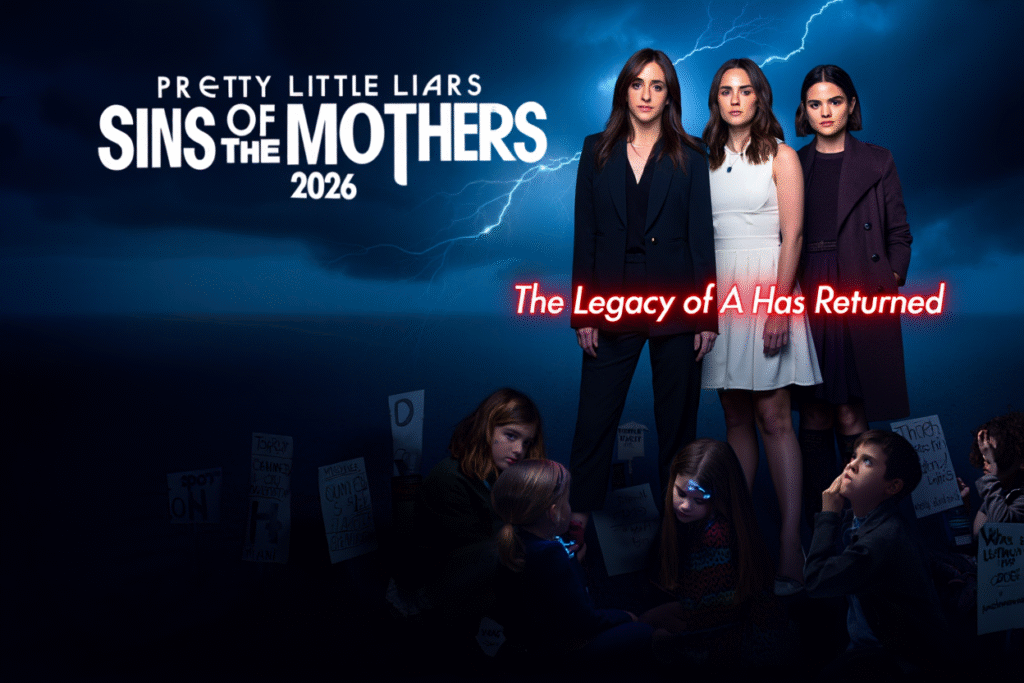

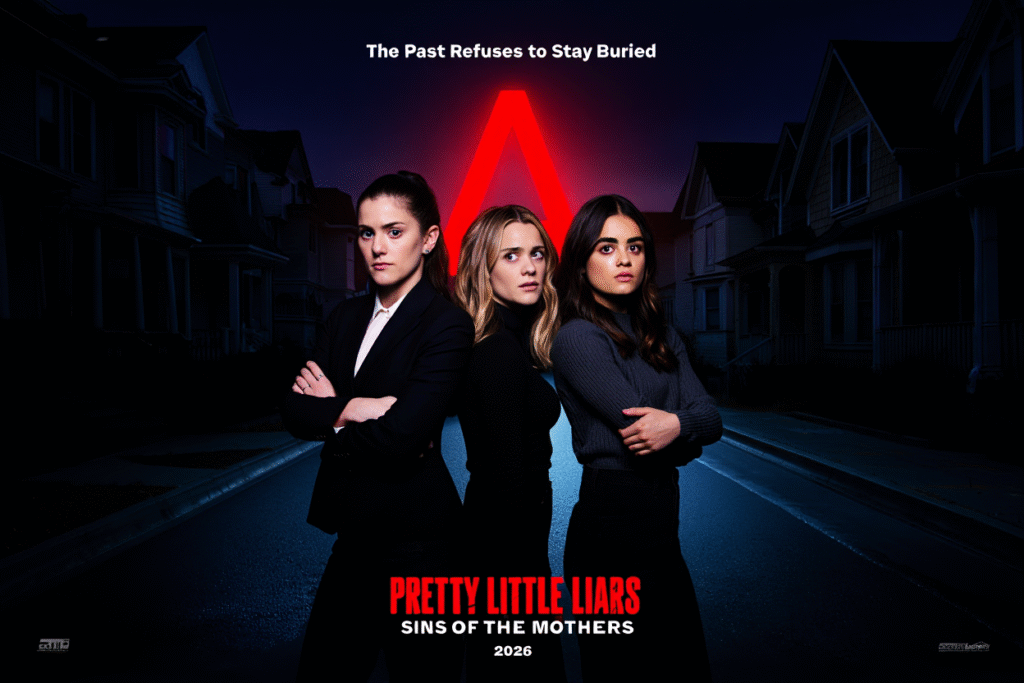

Pretty Little Liars: Sins of the Mothers is not a nostalgic return — it’s a chilling escalation. This sequel understands one brutal truth: the past never ends in Rosewood. It waits. And when it comes back, it doesn’t just target the guilty — it targets what they love most. From its opening moments, the film announces a darker, more emotionally devastating chapter in the PLL legacy.

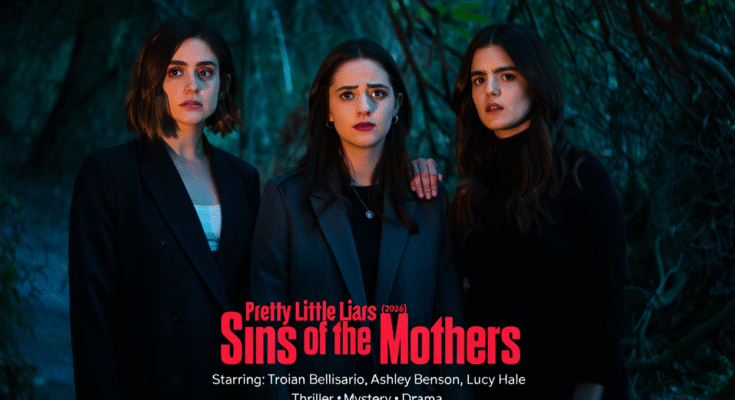

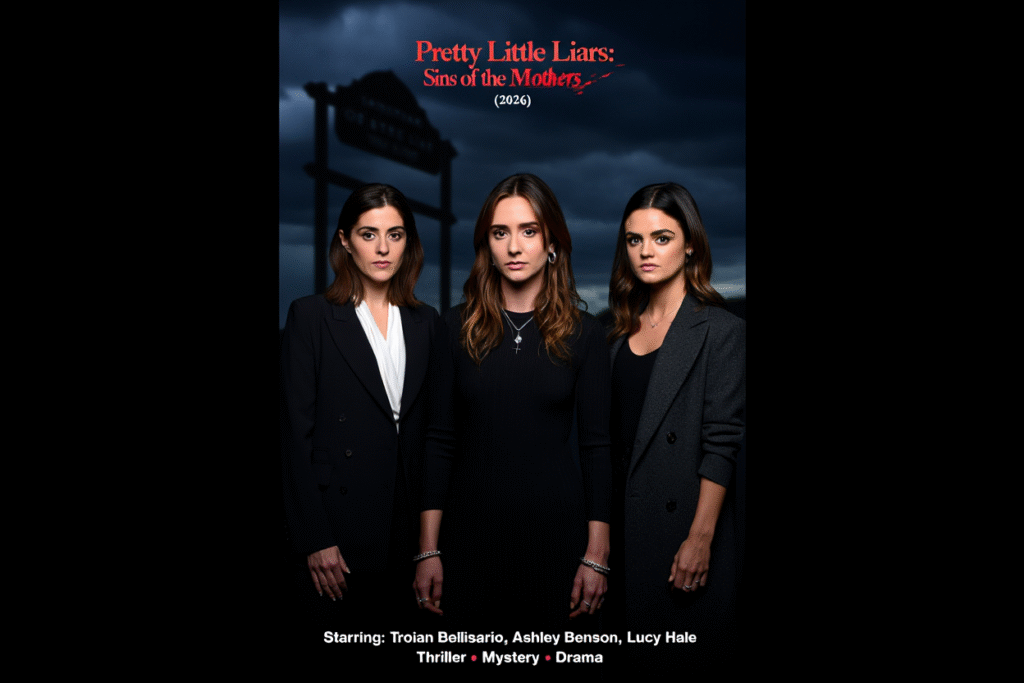

Spencer, Hanna, and Aria are no longer girls trapped by secrets; they are women who survived them. Troian Bellisario delivers a commanding performance as Spencer, now a disciplined attorney whose belief in justice begins to fracture when the law proves powerless against fear. Her control, once her greatest strength, becomes her most dangerous weakness.

Ashley Benson’s Hanna brings emotional volatility to the story. As a fashion powerhouse who has mastered image and influence, Hanna is confronted with the one thing she cannot style away — terror for her child. Benson plays Hanna with raw vulnerability, allowing fear and fury to coexist in every scene.

Lucy Hale’s Aria offers the film’s most haunting arc. As a bestselling author, Aria has turned trauma into fiction — but when her own words begin to mirror real-life threats, the line between imagination and guilt dissolves. Hale’s performance is quietly unsettling, filled with regret, denial, and creeping dread.

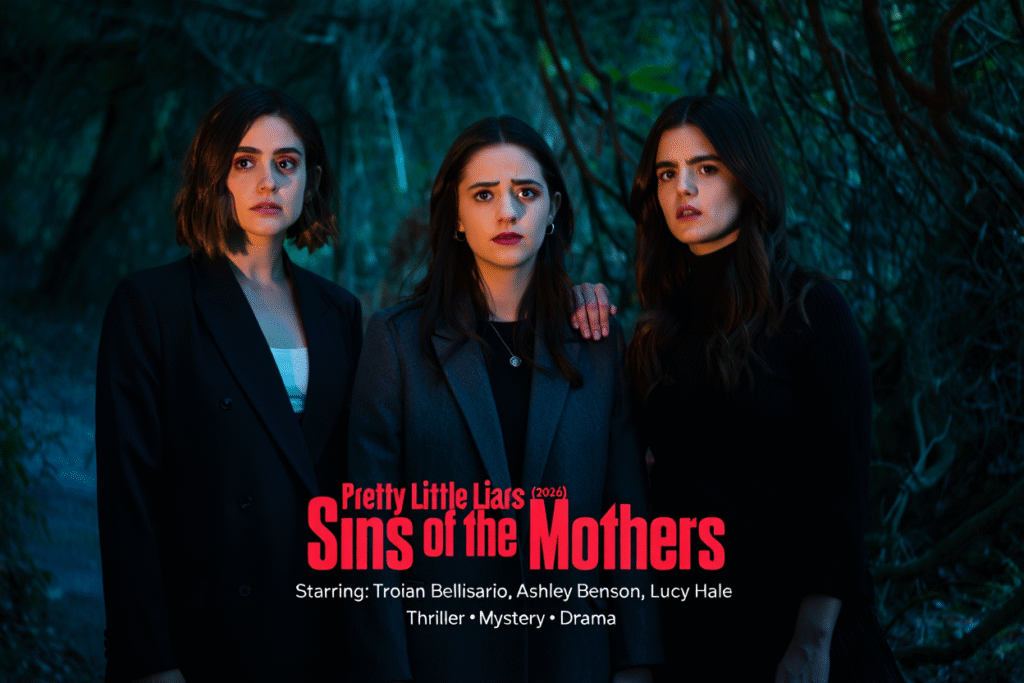

The decision to center the narrative on the Liars’ children is both bold and merciless. The new “A” isn’t interested in repeating the past — they’re refining it. This antagonist doesn’t merely torment; they manipulate legacy, using inherited sins as weapons. The message is clear: trauma doesn’t disappear — it mutates.

Rosewood itself feels transformed. Once a playground of secrets, it now feels like a mausoleum of unresolved guilt. The cinematography leans into shadow, silence, and stillness, allowing tension to breathe. Familiar locations feel corrupted, as if the town remembers everything the Liars tried to forget.

What makes Sins of the Mothers especially effective is its emotional maturity. The film doesn’t rely solely on jump scares or shock twists — it builds dread through responsibility, regret, and moral compromise. These women aren’t running from “A” anymore; they’re running from the consequences of who they used to be.

The mystery unfolds with calculated patience. Clues are layered, red herrings are emotionally charged, and revelations hit hardest when they force the Liars to question their own narratives. Every answer opens a deeper wound, reinforcing the idea that truth is rarely clean.

The new “A” is one of the franchise’s most disturbing creations — not because of spectacle, but because of precision. They know when to strike, what to say, and how to turn love into leverage. This is not a villain seeking revenge; this is someone seeking annihilation.

By the final act, the film sheds any illusion of safety. Choices carry irreversible consequences, alliances fracture, and the Liars are forced to confront an unbearable question: how far are you willing to go to save your child — and what part of yourself are you willing to lose?

Pretty Little Liars: Sins of the Mothers is darker, smarter, and more emotionally ruthless than anything that came before it. It transforms secrets into inheritance and survival into sacrifice. This is not a story about escaping the past — it’s about paying its final price.