Empire of the Summer Moon (2026) is not an easy film to watch—and it isn’t meant to be. Directed with raw intensity by Taylor Sheridan, this historical western strips away romantic myths of the American frontier and replaces them with a brutal, unflinching portrait of conquest, resistance, and cultural erasure. From its opening moments, the film makes one thing clear: this is a story about power, survival, and the people history tried to silence.

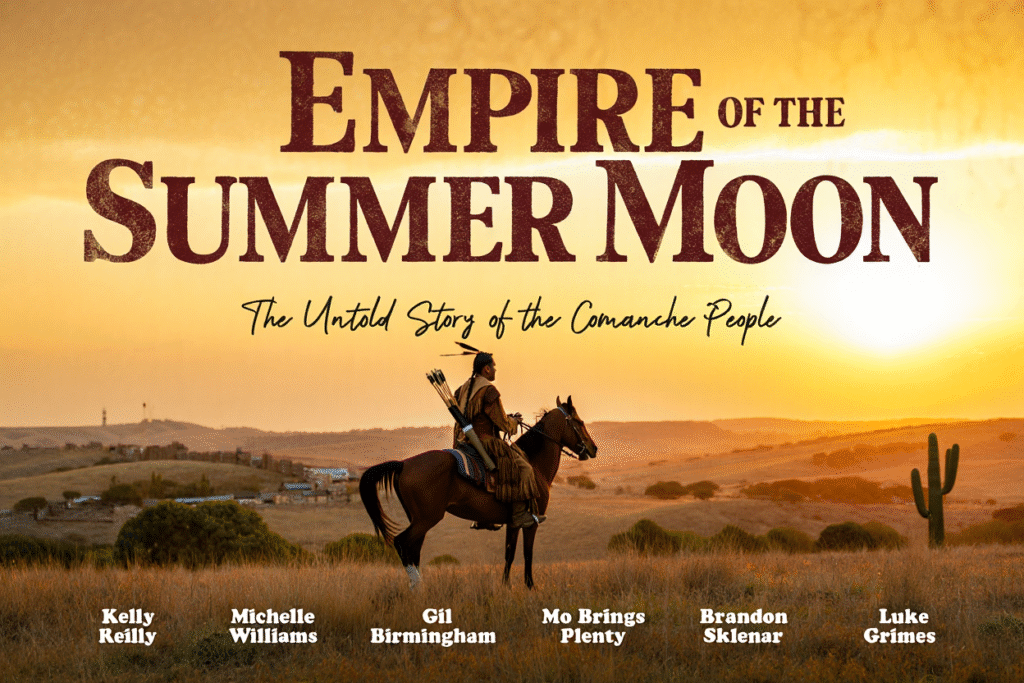

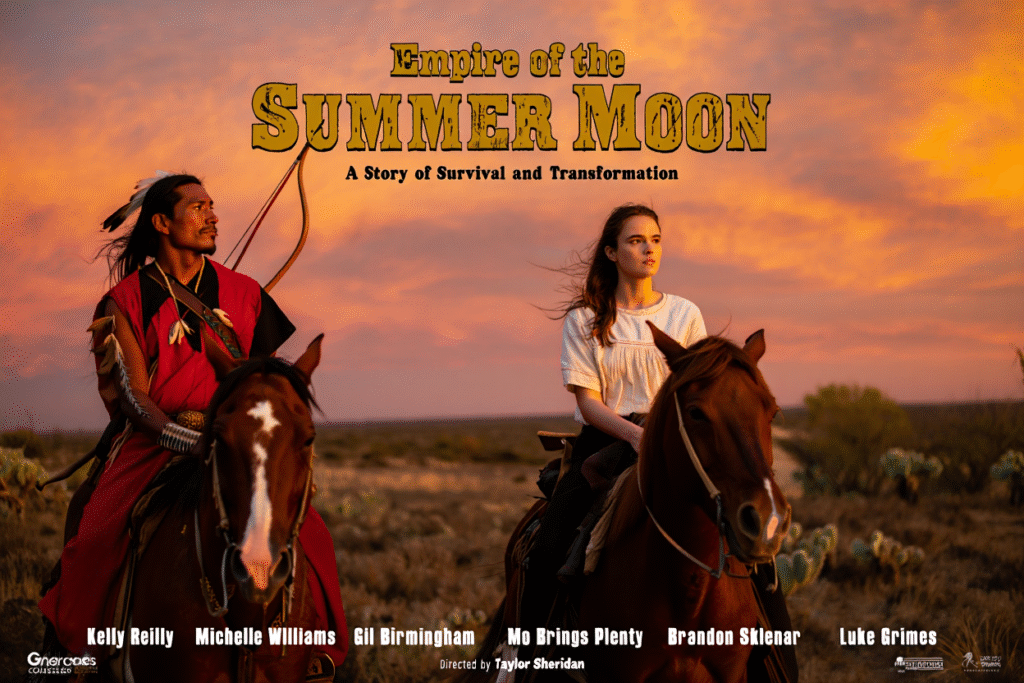

At the heart of the film stands the Comanche Nation, portrayed not as background figures in a settler narrative, but as the central force shaping the fate of the Southern Plains. Sheridan reframes the West as an empire long before America claimed it—one ruled by Comanche warriors whose mastery of land, horses, and warfare made them nearly unstoppable for decades. The title itself feels heavy, poetic, and ominous, signaling both dominance and impermanence.

Quanah Parker emerges as the film’s moral and emotional spine. His journey—from a fierce warrior forged in violence to a leader forced into diplomacy—captures the impossible choices faced by indigenous leaders during westward expansion. The performance is grounded and restrained, allowing Quanah’s intelligence and internal conflict to speak louder than grand speeches. He is not idealized, but deeply human.

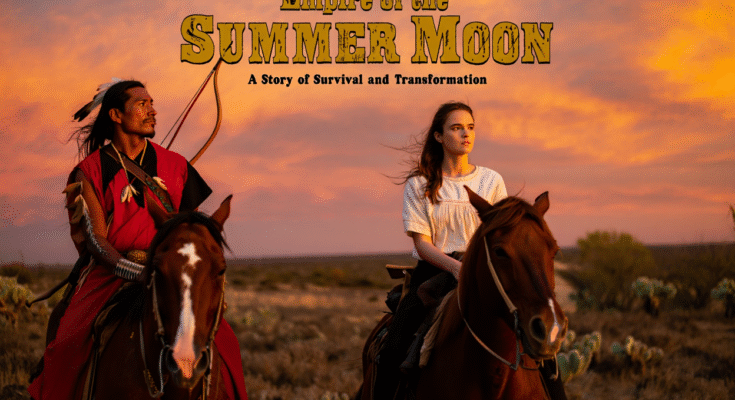

Cynthia Ann Parker’s story is where the film cuts deepest. Whether played by Kelly Reilly or Michelle Williams, her portrayal is haunting and quietly devastating. Abducted as a child and raised Comanche, Cynthia’s identity becomes a battleground between two worlds that refuse to understand each other. Her tragedy lies not in where she belongs, but in the fact that belonging itself is denied to her.

The film refuses simple binaries. Violence is shown from every side, stripped of heroism and drenched in consequence. Settlers are not cartoon villains, nor are the Comanche portrayed as noble stereotypes. Instead, Empire of the Summer Moon presents history as collision—cultures moving toward each other with incompatible values and devastating results.

Visually, the film is staggering. Shot on the 6666 Ranch, the wide Texas landscapes feel both majestic and merciless. Endless plains stretch like open wounds, emphasizing how small human lives are against land that remembers everything. Sheridan uses silence as effectively as gunfire, letting the environment speak when words fail.

Gil Birmingham and Mo Brings Plenty bring profound gravity to the supporting cast, anchoring the film in indigenous perspective and tradition. Their presence adds emotional legitimacy, ensuring the story never drifts into exploitation. These are performances rooted in generational memory, not just scripted dialogue.

Luke Grimes and Brandon Sklenar embody the encroaching frontier—men shaped by ambition, fear, and ideology. They are not glorified, but contextualized, representing a system larger than any single individual. The film smartly suggests that history’s cruelty often comes from momentum, not malice alone.

What truly separates this film from other westerns is its patience. Sheridan allows the story to unfold over decades, letting the audience feel the slow erosion of a people’s world. Time becomes an antagonist—relentless, unavoidable, and devastating.

There are no triumphant endings here, only survival. The final act lands with a quiet, aching weight, forcing the audience to confront what was lost in the name of progress. The film does not ask for forgiveness, nor does it offer closure—it demands remembrance.

Empire of the Summer Moon is powerful, unsettling, and necessary. It challenges viewers to rethink the mythology of the American West and to acknowledge that empires rise and fall on human cost. This is not just a historical film—it’s a reckoning, and it lingers long after the screen goes dark.