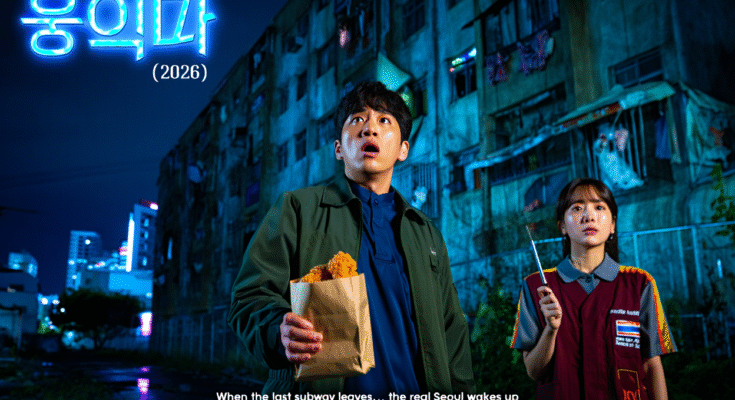

Seoul After Midnight (2026) is the kind of genre-blending film that sneaks up on you quietly, then grabs you by the collar once the last subway has gone home. What begins as a familiar urban horror setup quickly mutates into something far richer: a comedy-horror that understands both the fear and absurdity of modern city life, especially in a city that never truly sleeps.

Lee Kwang-soo is perfectly cast as Joon-woo, a man whose exhaustion feels universal. As a food delivery driver scraping by on late-night orders, he embodies a generation stuck between survival and stagnation. His accidental acceptance of a cursed delivery is funny not because it’s exaggerated, but because it feels painfully believable—who hasn’t ignored a red flag when rent is due?

The film’s central location, an abandoned apartment complex awaiting demolition, is where Seoul After Midnight truly comes alive. Rather than leaning solely into decay and dread, the building becomes a surreal playground. Elevators disobey logic, hallways stretch like bad dreams, and yet the space is filled with bickering ghosts arguing about food orders and outdated technology. Horror and comedy coexist naturally, never canceling each other out.

Kim Se-jeong’s Ara is a standout, bringing sharp wit and unexpected emotional grounding to the chaos. As a part-time exorcist who treats the supernatural like a customer service job, she reframes the spirits not as monsters, but as unresolved people. Her chemistry with Lee Kwang-soo fuels much of the film’s humor while quietly anchoring its heart.

Park Sung-woong steals scenes as the gangster ghost turned afterlife landlord, a character that could have been a caricature but instead becomes strangely endearing. His obsession with rules, order, and hierarchy in death mirrors the rigid systems he lived by in life, adding a layer of satire beneath the laughs.

Honey Lee’s glamorous pop star spirit injects the film with neon nostalgia and melancholy. Her fixation on unfinished fame is played for laughs at first, but slowly reveals a sadness that resonates deeply in a culture obsessed with relevance and visibility. Her character becomes one of the film’s most poignant reflections on legacy.

What makes the comedy work is restraint. The film never turns the ghosts into cheap punchlines. Even the most absurd moments—accidental possessions, botched rituals, spectral tantrums—are rooted in emotional truth. The humor feels human, not dismissive of the horror elements.

Visually, Seoul After Midnight is stylish without being flashy. Neon-lit rooftops, dim corridors, and flickering convenience store lights create a uniquely Korean urban atmosphere. The city feels alive even in its quietest hours, reinforcing the idea that Seoul has a pulse that continues long after midnight.

The pacing is fast but deliberate, balancing slapstick chaos with moments of stillness. When the film pauses, it does so to let regret surface. These ghosts aren’t trapped because they’re evil—they’re trapped because they couldn’t let go, a theme that subtly mirrors Joon-woo’s own fear of going nowhere in life.

At its core, the film is about second chances. Not just for the dead, but for the living who are too tired, too afraid, or too distracted to confront their own unresolved lives. Helping the ghosts becomes a way for Joon-woo to finally face his own inertia.

Seoul After Midnight proves that comedy-horror doesn’t need to choose between laughs and meaning. It delivers both, wrapped in supernatural chaos and late-night Seoul charm. When the sun finally rises, you’re left smiling—not because the fear is gone, but because even in the strangest hours, connection is still possible.