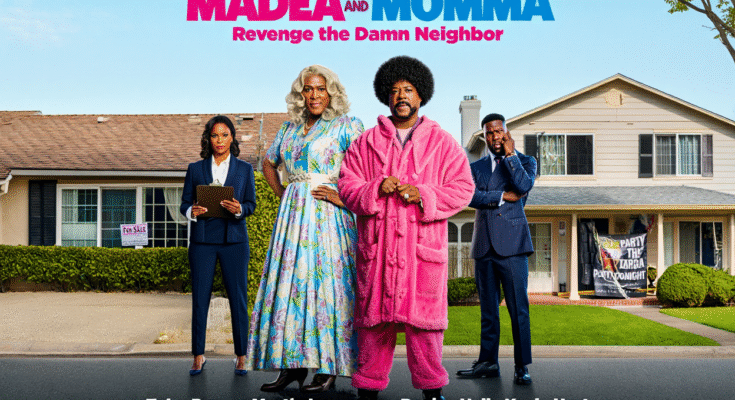

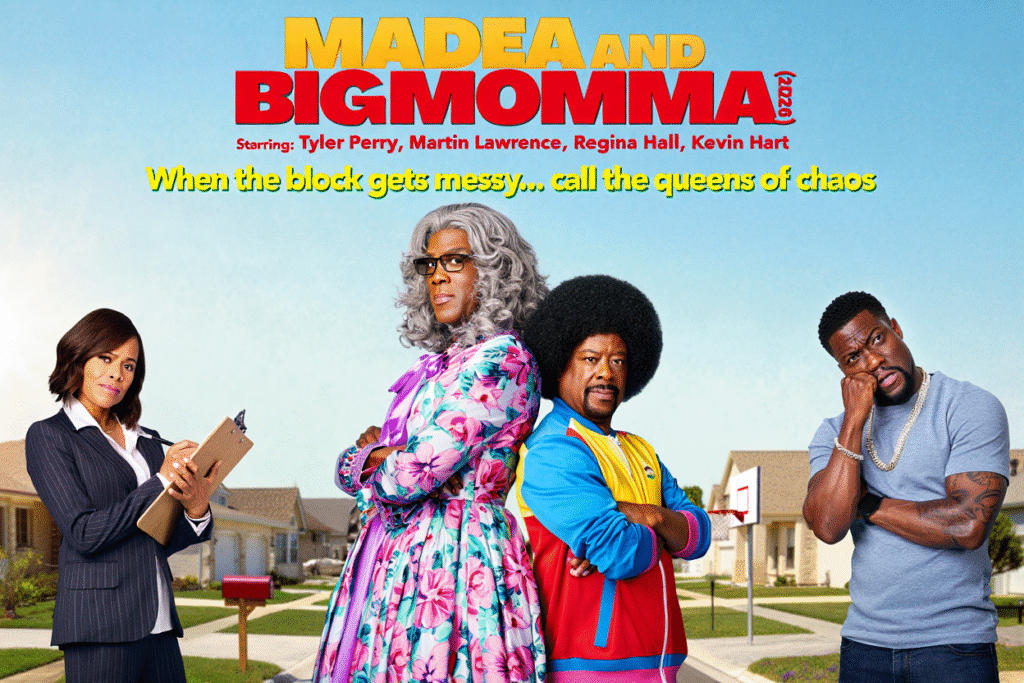

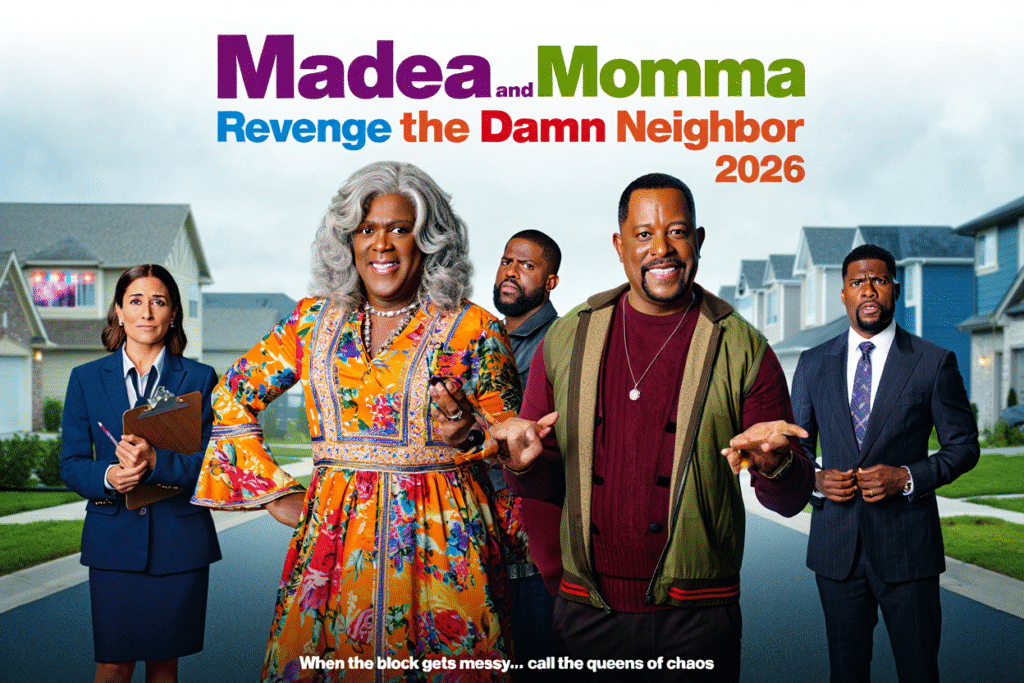

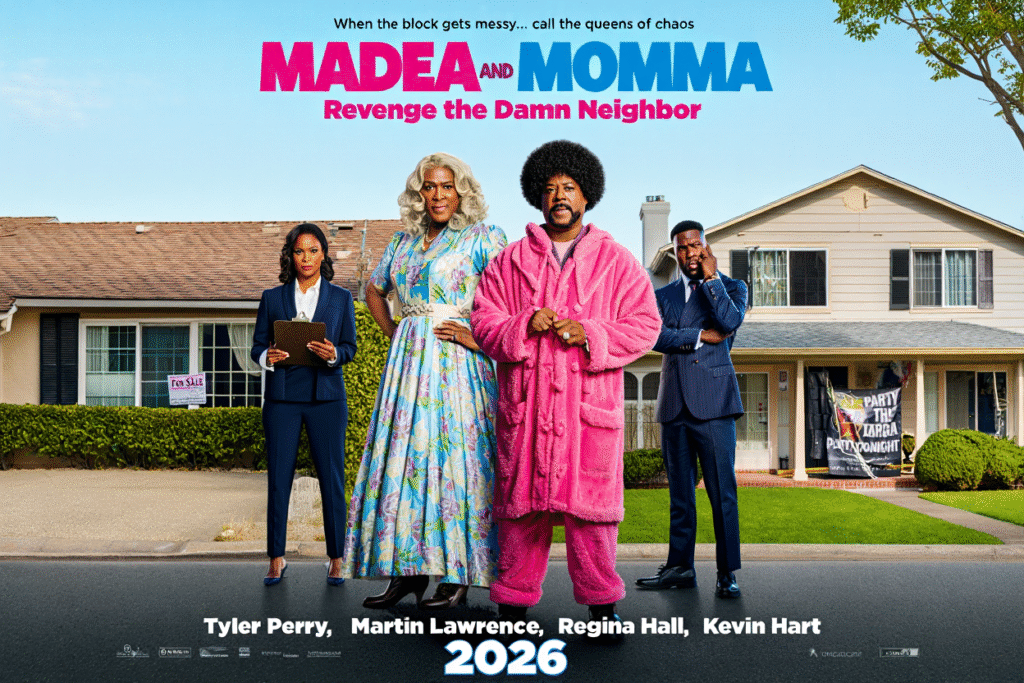

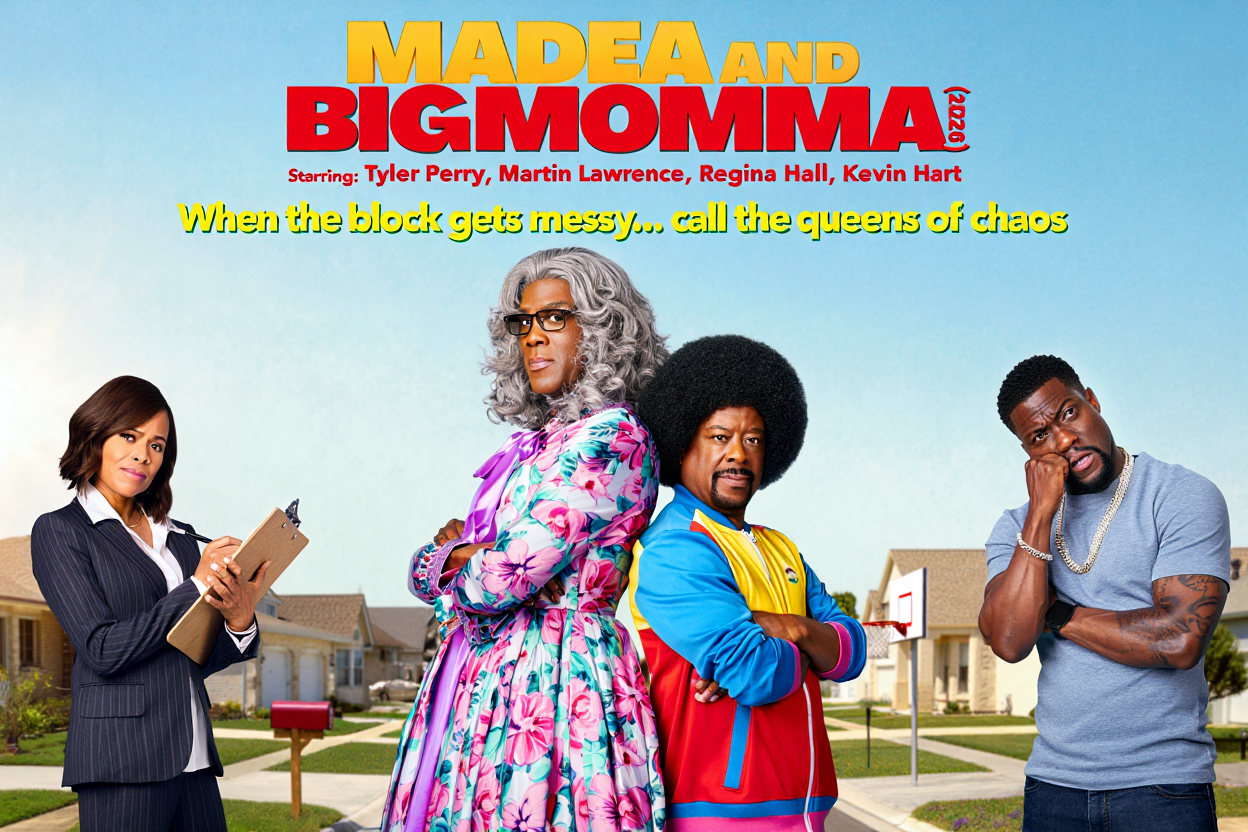

Madea and Big Momma: Revenge the Damn Neighbor (2026) is exactly the kind of crossover comedy that knows its audience and proudly refuses to behave. From the moment Tyler Perry’s Madea and Martin Lawrence’s Big Momma share the screen, the film announces its mission clearly: loud laughs, unapologetic chaos, and a surprising amount of heart beneath the wigs, purses, and side-eyes.

The premise is delightfully simple but dangerously effective. Two iconic comedic matriarchs, accidentally turned neighbors, find themselves forced into an uneasy coexistence. Their rivalry is instant, personal, and hysterical—every interaction feels like a verbal sparring match where no one walks away unscathed. The film milks this tension expertly before giving audiences what they really want: unity forged through shared annoyance.

Enter the “damn neighbor,” a slick, overconfident disruptor whose presence feels wrong from the start. He’s not just noisy or rude—he represents intrusion, entitlement, and disrespect for community. The movie smartly positions him as more than a joke villain; he’s a symbol of the kind of chaos that threatens the fabric of the neighborhood, giving the comedy a surprisingly grounded motivation.

Tyler Perry is in peak Madea form here, firing off insults like warning shots and wielding her purse like a moral weapon. Madea isn’t softened or sentimentalized—she’s sharp, aggressive, and protective. This version of the character feels purpose-built for confrontation, and Perry leans into the physical comedy just as much as the verbal fireworks.

Martin Lawrence’s Big Momma, meanwhile, brings a contrasting energy that balances the madness. Where Madea is explosive, Big Momma is strategic. Lawrence plays her with a mix of warmth and intimidation, delivering lines that feel playful on the surface but carry an unmistakable threat underneath. Watching these two icons circle each other before finally teaming up is pure comedic payoff.

Regina Hall adds a strong supporting presence as the exhausted neighborhood association president, grounding the film just enough to keep it from floating off into pure absurdity. Her character’s desperate attempts to maintain order become an ongoing joke—and a subtle reminder that even chaos needs boundaries. She plays the straight woman without ever feeling dull.

Kevin Hart, as expected, injects frantic energy into every scene he’s in. His role as the fast-talking assistant caught between all sides allows him to function as both instigator and victim. Hart’s physical comedy shines here, especially during undercover sequences where fear, overconfidence, and regret collide in rapid succession.

The film’s set pieces are unapologetically ridiculous—and proudly so. Costume disguises that make no sense, cookout confrontations that escalate into public spectacles, and a mobility scooter chase that has no right being as funny as it is all contribute to the movie’s commitment to excess. This is comedy that doesn’t whisper—it shouts.

What surprisingly works best, though, is the bond that forms between Madea and Big Momma. Beneath the insults and power struggles is a shared sense of responsibility. These women don’t just want revenge—they want to protect their block, their people, and the idea that community still matters. That emotional throughline keeps the film from feeling hollow.

Visually and tonally, Revenge the Damn Neighbor doesn’t aim for polish; it aims for energy. The pacing is fast, the dialogue relentless, and the jokes frequent enough that even when one misses, another lands seconds later. It understands that momentum is everything in broad comedy.

In the end, Madea and Big Momma: Revenge the Damn Neighbor is exactly what it promises: a loud, chaotic, crowd-pleasing comedy that thrives on personality over subtlety. It’s not trying to reinvent the genre—it’s celebrating it. When the block gets messy, these queens don’t just clean it up. They own it.