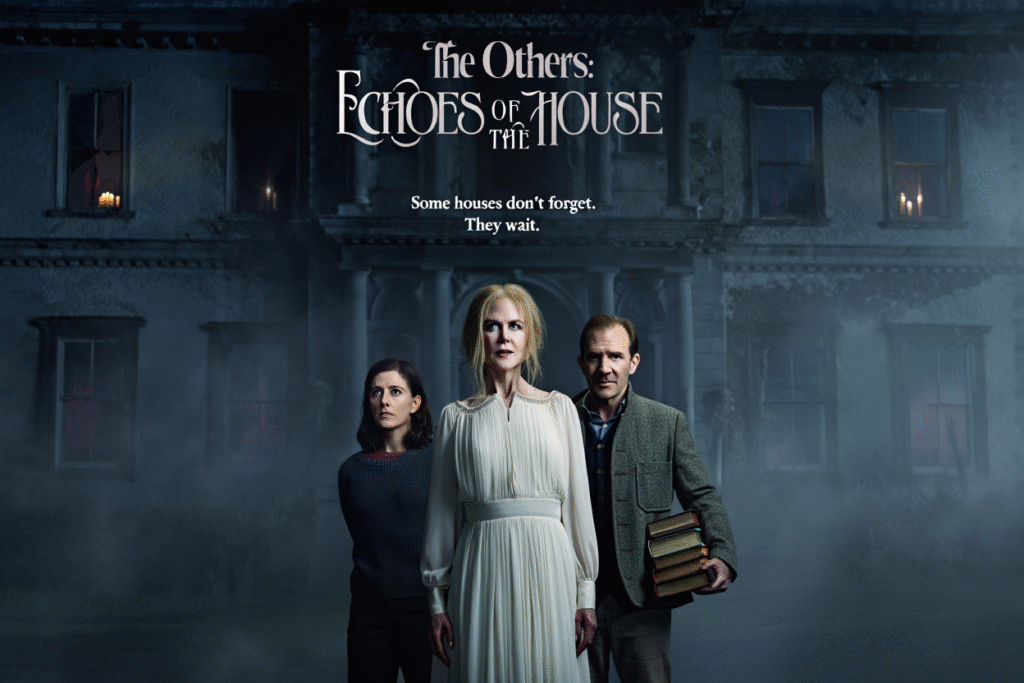

The Others: Echoes of the House (2027) is not a sequel that seeks to shock through reinvention. Instead, it haunts by remembering. Returning to the fog-drenched estate more than two decades after Alejandro Amenábar’s original masterpiece, this film understands exactly what made The Others endure: restraint, grief, and the unbearable weight of denial.

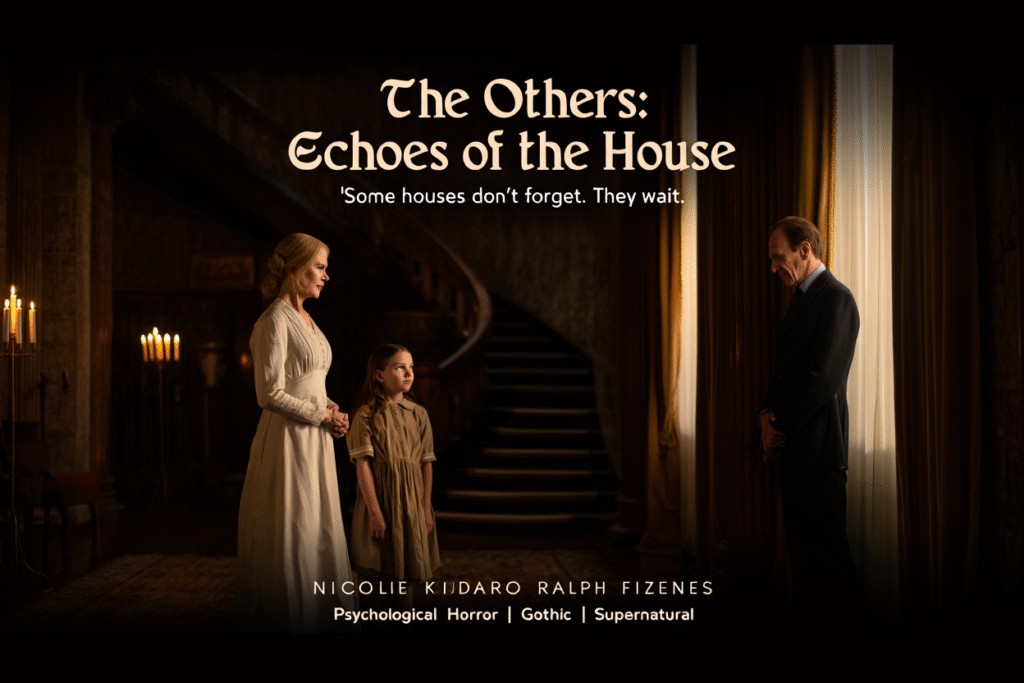

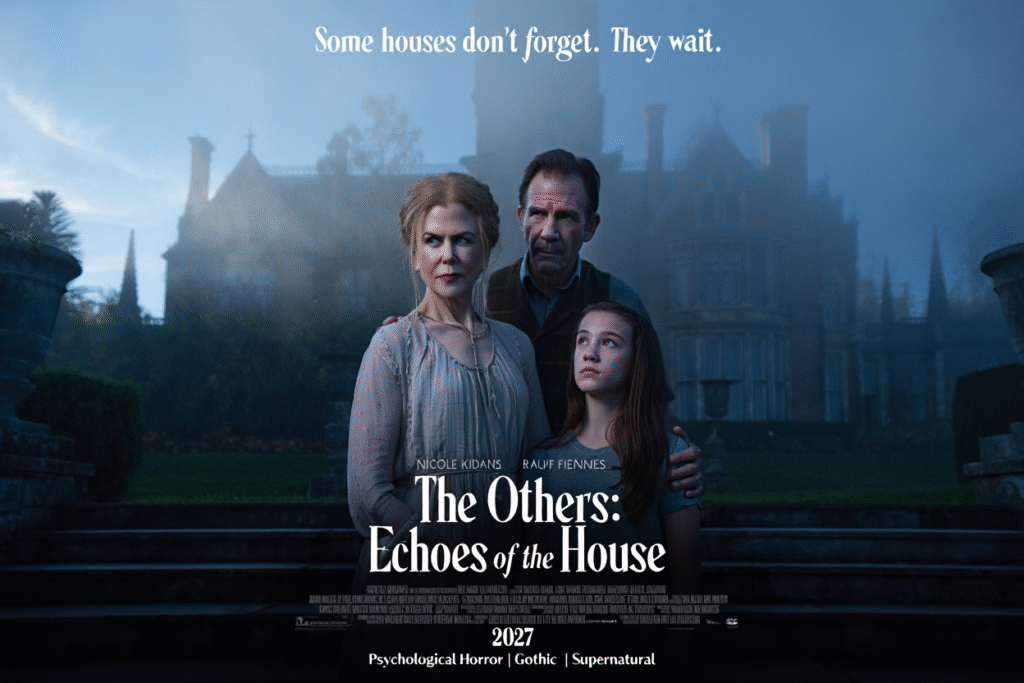

Nicole Kidman’s return as Grace Stewart is the film’s emotional and thematic anchor. This is not the fragile, tightly wound woman we once knew, but a soul suspended in awareness — neither at peace nor fully damned. Kidman plays Grace with devastating stillness, her performance defined by silence, by glances that carry decades of unresolved sorrow. She doesn’t command the screen; she lingers on it, like a memory you cannot shake.

The introduction of Ralph Fiennes as a grieving historian brings a grounded, intellectual energy into the story. His character approaches the house as an object to be studied, cataloged, understood — a fatal mistake in a place that resists being defined. Fiennes excels at portraying rationality cracking under pressure, his disbelief slowly corroded by things that cannot be footnoted or explained away.

Thomasin McKenzie is extraordinary as his withdrawn teenage daughter, serving as the emotional bridge between worlds. Her sensitivity never feels like a horror cliché; instead, it’s rooted in grief and introspection. McKenzie’s performance suggests that some people don’t see ghosts — they feel them first. Her quiet fear is far more unsettling than screams ever could be.

What distinguishes Echoes of the House is its refusal to rely on a singular twist. The original film famously reshaped our understanding of its world in one devastating revelation. Here, the horror unfolds through accumulation. Each moment — a door closing gently, a blurred photograph, a staircase vigil — adds another layer to a suffocating sense of inevitability.

The house itself is the film’s most frightening presence. Shot with reverence and menace, its corridors feel narrower, its ceilings lower, its silence heavier. This is not a backdrop but an entity — one that observes, remembers, and feeds. The idea that the house is not haunted but hungry is the film’s most chilling evolution of the mythology.

Grace’s conflict is no longer about denial, but possession. She believes protecting her children means holding the house forever, even as she begins to realize that her attachment may be the very thing sustaining the evil within its walls. This internal struggle gives the film its tragic power: love, once pure, has become a cage.

The score is sparse yet relentless, pulsing like a distant heartbeat through empty rooms. Sound design is used with surgical precision — footsteps echo too long, silence stretches too wide. The film understands that fear often comes not from what enters the frame, but from what refuses to.

Visually, Echoes of the House embraces gothic melancholy rather than modern horror aesthetics. Candlelight replaces jump scares. Fog obscures rather than reveals. The palette is drained, as if color itself has been leached away by time and sorrow. Every frame feels suspended between centuries.

The final act is devastating in its restraint. There is no triumph, no cleansing fire, no easy resolution. Grace’s ultimate confrontation is not with a demon or an intruder, but with the concept of release itself. Letting go, the film argues, may be the most terrifying act of all.

The Others: Echoes of the House is not interested in reinventing horror — it refines it. This is a sequel built on emotional intelligence, atmospheric patience, and the courage to embrace sadness as its greatest weapon. It lingers long after the screen fades to black, whispering the same unbearable truth: some places don’t trap us. We choose to stay.