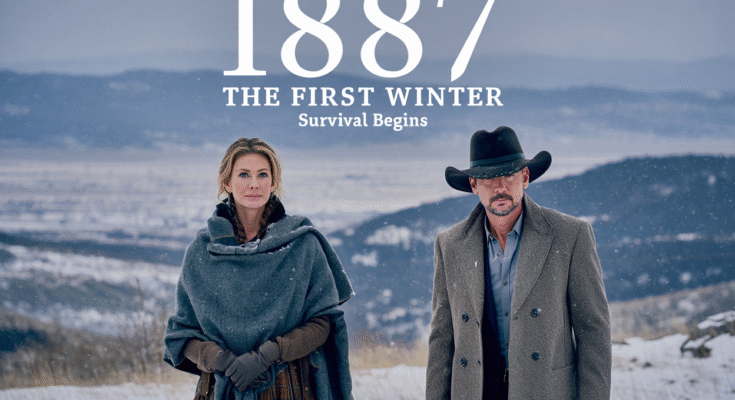

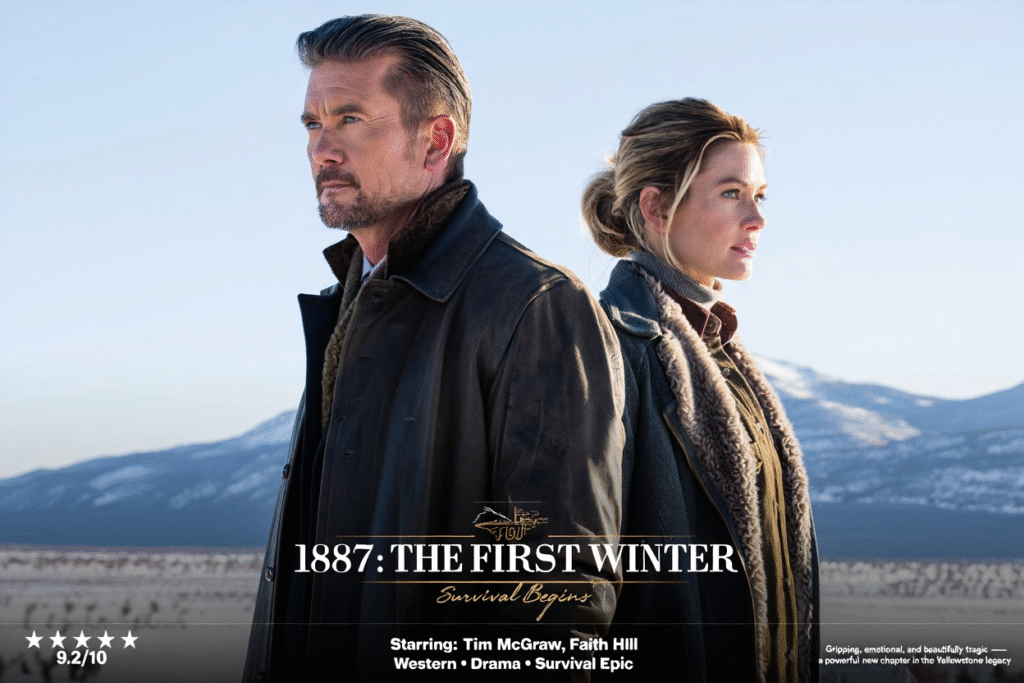

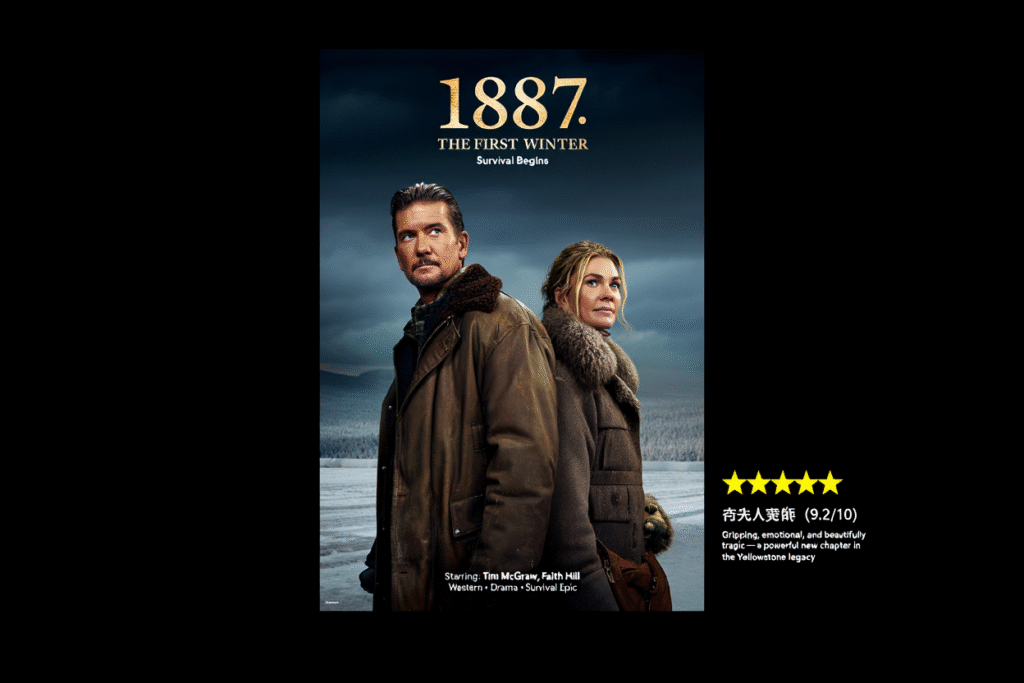

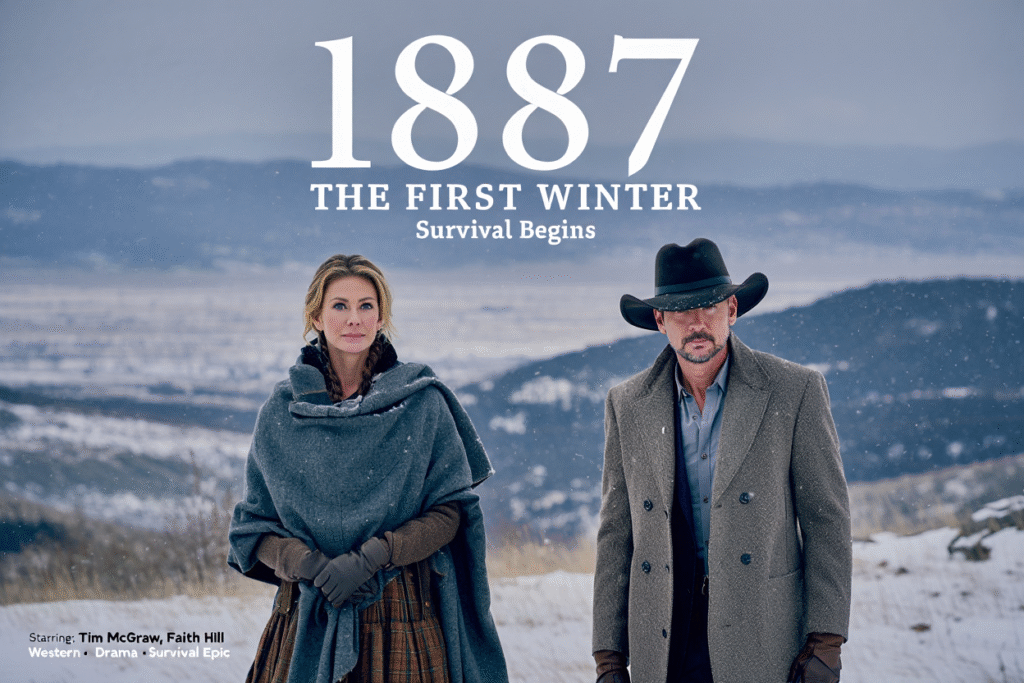

If 1883 was a story of hope and migration, 1887: The First Winter is a story of endurance and reckoning. Set four years after the Duttons’ long and bloody journey west, this starkly beautiful follow-up trades the sun-scorched plains for the merciless snows of Montana — a land that tests not only the body, but the very spirit of those who dare to call it home. Starring Tim McGraw and Faith Hill in their most emotionally raw performances to date, 1887: The First Winter is not merely a Western — it’s an elegy for survival, love, and the cost of building an empire out of wilderness and willpower.

From its opening scene — a sweeping shot of the Dutton homestead buried beneath endless white — the film grips you in its silence. The wind howls like memory itself, and the world feels impossibly vast, indifferent, and hungry. James Dutton (McGraw), now older and visibly worn, moves through the snow like a ghost still chasing a dream that might already be dead. Margaret (Hill), equal parts steel and grace, becomes the family’s anchor — her strength not loud or defiant, but patient, enduring, and heartbreakingly human.

The first act builds slowly, with director Taylor Sheridan’s trademark patience. We watch the Duttons patch roofs, bury livestock, and ration dwindling supplies while the camera lingers on the quiet brutality of the landscape. Snow becomes both antagonist and metaphor — purity masking danger, beauty hiding death. The cinematography by Ben Richardson is breathtaking, every frame a painting in frost and firelight. Sheridan’s dialogue is spare but poetic, echoing like prayers whispered through cold air.

What makes 1887: The First Winter so haunting isn’t just its depiction of physical hardship, but its emotional honesty. This is a family still mourning the ghosts of 1883 — the children they lost, the friends buried along the trail, the innocence traded for survival. Those ghosts walk with them still, appearing in dreams and in the flicker of firelight. One haunting sequence finds James stumbling into a snowstorm and encountering what may or may not be the spirit of Elsa, her voice carried by the wind. It’s a devastating reminder that the Duttons’ real battle is not just against the elements, but against grief that refuses to thaw.

As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that winter is not their only enemy. Tensions rise with neighboring settlers, desperate and starving men who would rather steal than starve. Sheridan avoids clichés, grounding the conflict in moral ambiguity — a brutal world where right and wrong are separated by nothing but hunger. In one gut-wrenching scene, James must choose between sharing his last horse or protecting his family. His decision, and its consequences, define the film’s bleak, beautiful soul.

Faith Hill’s Margaret is the film’s beating heart. Her performance is mesmerizing — quiet but volcanic, radiating both fear and faith. She carries her family through the storm with stubborn tenderness, her prayers a lifeline between the living and the lost. In one unforgettable monologue, she kneels in the snow beside a frozen stream and confesses to God that she’s not praying for survival anymore, only for meaning. It’s the kind of scene that lingers long after the credits roll — raw, spiritual, and utterly human.

The score, composed by Brian Tyler, swells like the land itself — sparse violins, aching piano, and the occasional mournful harmonica that echoes across empty fields. It’s less a soundtrack and more a lament, underlining the film’s central theme: survival is not victory; it’s endurance without promise.

By its final act, 1887: The First Winter transforms from survival drama into something mythic. As a final blizzard bears down on the Duttons, they gather in their small cabin, the fire nearly out, whispering stories to keep the dark at bay. It’s in that firelit circle — where love becomes both shield and surrender — that Sheridan finds the essence of the Western myth: that civilization was built not by conquest, but by those who refused to stop loving in the face of despair.

When dawn finally breaks, the world outside is quiet, pale, and reborn. Not everyone survives the night, and those who do are changed forever. James and Margaret step into the sunlight — not triumphant, but still standing, still together. Their farm, battered but standing, becomes the seed from which generations will grow — and with it, the beginning of the Yellowstone legacy.

1887: The First Winter is not an action-packed Western; it’s a meditation on endurance, faith, and the weight of dreams. It burns slow and cold, its power hidden beneath silence and snowfall. Every moment feels earned, every sacrifice grounded in truth.

In the end, Sheridan delivers not just a prequel chapter, but a haunting reflection on what it means to survive when hope itself feels frozen. For fans of 1883 and Yellowstone, this film deepens the Dutton mythos with grace and grit. For everyone else, it stands as a cinematic monument to human resilience — to love that refuses to die, even when everything else does.