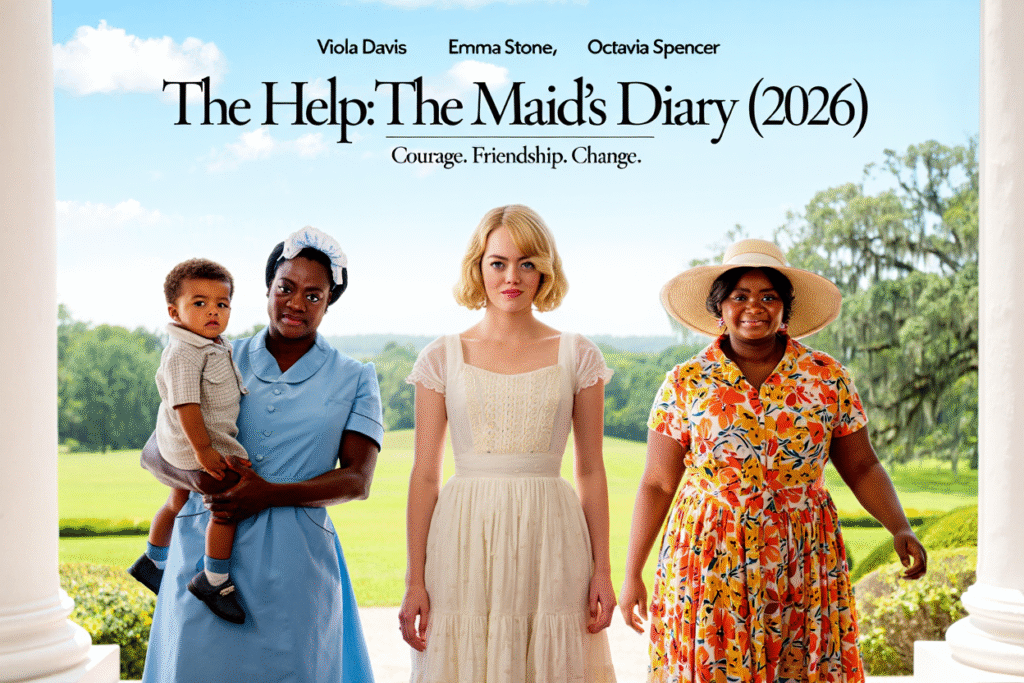

The Help: The Maid’s Diary (2026) is not merely a continuation of a beloved story—it is a deeper, more intimate reckoning with history, memory, and moral courage. Set once again in 1960s Mississippi, the film shifts its emotional center inward, transforming collective testimony into something profoundly personal. This time, the story is framed through Aibileen’s private diary, giving the audience direct access to the thoughts she was never allowed to speak aloud.

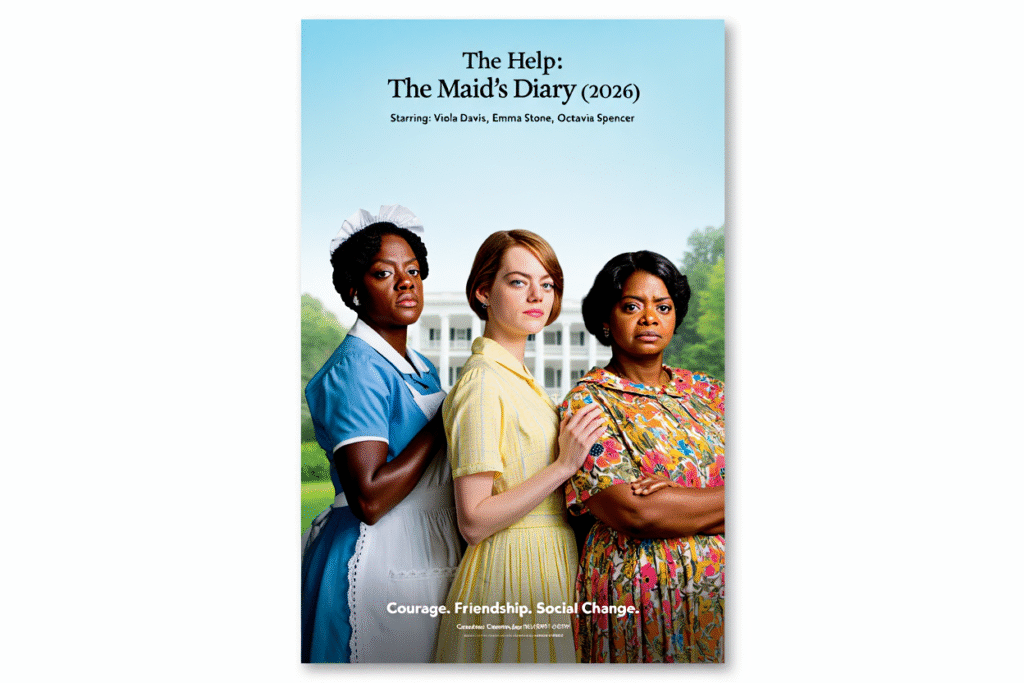

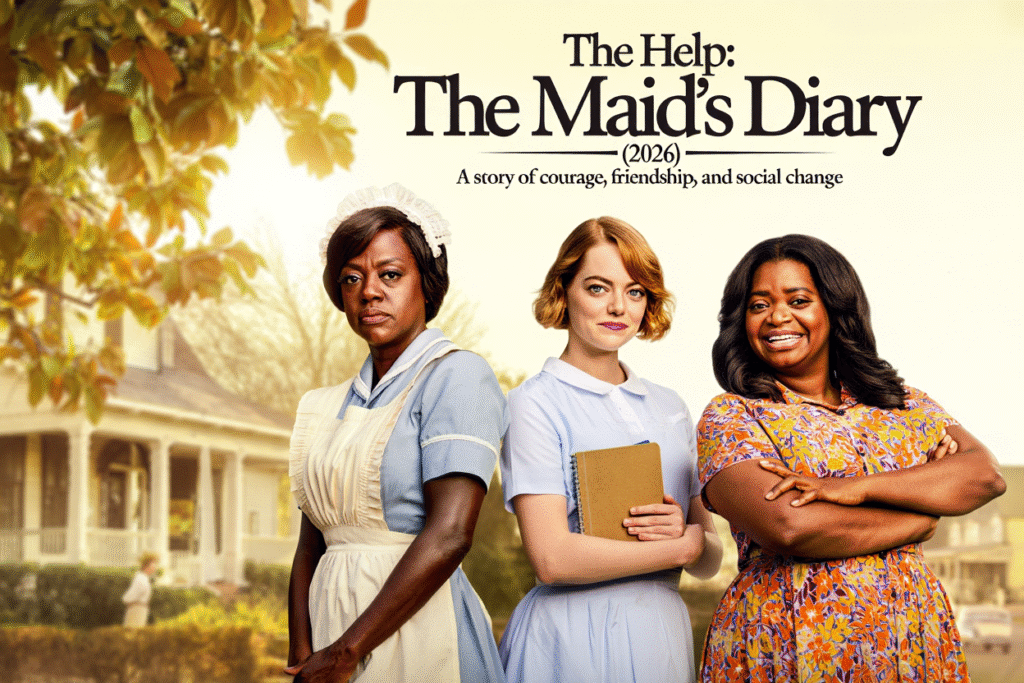

Viola Davis delivers a performance of staggering quiet power. As Aibileen, she is older, wearier, but no less dignified, carrying the emotional weight of a lifetime spent loving children who were never hers while being denied basic human respect. Davis uses silence as her strongest weapon, allowing every pause and glance to speak volumes about suppressed pain and enduring grace.

Emma Stone’s Skeeter returns with a maturity that reflects the cost of awakening. No longer driven by youthful rebellion alone, she now understands the danger her work places on the women who trust her. Stone plays Skeeter with restraint, letting guilt, fear, and determination coexist in a way that feels earned rather than heroic.

Octavia Spencer once again ignites the screen as Minny, whose sharp tongue remains intact but is now sharpened by consequence. Her humor is still present, but it is tinged with exhaustion and defiance, reminding us that bravery often comes wrapped in anger. Spencer’s performance balances levity and rage, making Minny both disarming and devastating.

What distinguishes The Maid’s Diary is its narrative structure. By centering the story around written confessions never meant to be read, the film creates a sense of intimacy that is almost uncomfortable. These diary entries feel like stolen truths, forcing the audience to sit with the emotional cost of survival under systemic cruelty.

The film does not soften its portrayal of segregation. Everyday humiliations—separate bathrooms, whispered threats, performative kindness—are depicted with unflinching clarity. Yet the violence here is often emotional rather than physical, making it linger longer and cut deeper.

Cinematography plays a crucial role in reinforcing this tension. Muted color palettes dominate domestic spaces, while moments of truth and solidarity are bathed in warmer light. This visual contrast subtly mirrors the dual lives these women are forced to live: obedient on the surface, revolutionary in private.

At its core, the film is about sisterhood—not as an idealized bond, but as a fragile, risky alliance forged under pressure. Trust is never guaranteed, and betrayal is always a possibility. That uncertainty gives the relationships emotional authenticity and moral weight.

The pacing is deliberate, allowing scenes to breathe and emotions to settle. Rather than rushing toward triumph, the film understands that progress is incremental and often invisible. Victories here are small but meaningful, measured in moments of dignity rather than applause.

Importantly, The Help: The Maid’s Diary avoids the trap of nostalgia. It does not look back with comfort, but with responsibility. The film repeatedly asks what it means to remember—and who gets to tell the story when history is written.

By the time the final pages of the diary are revealed, the film leaves the audience not with closure, but with obligation. The Help: The Maid’s Diary (2026) is a haunting, necessary reminder that courage does not always roar—sometimes, it is written quietly, one forbidden truth at a time.