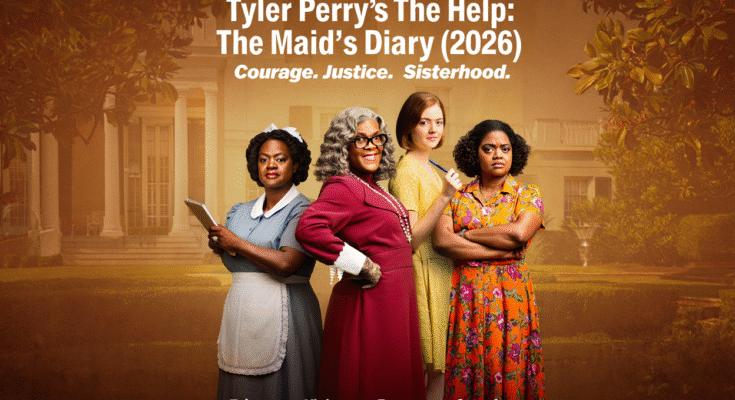

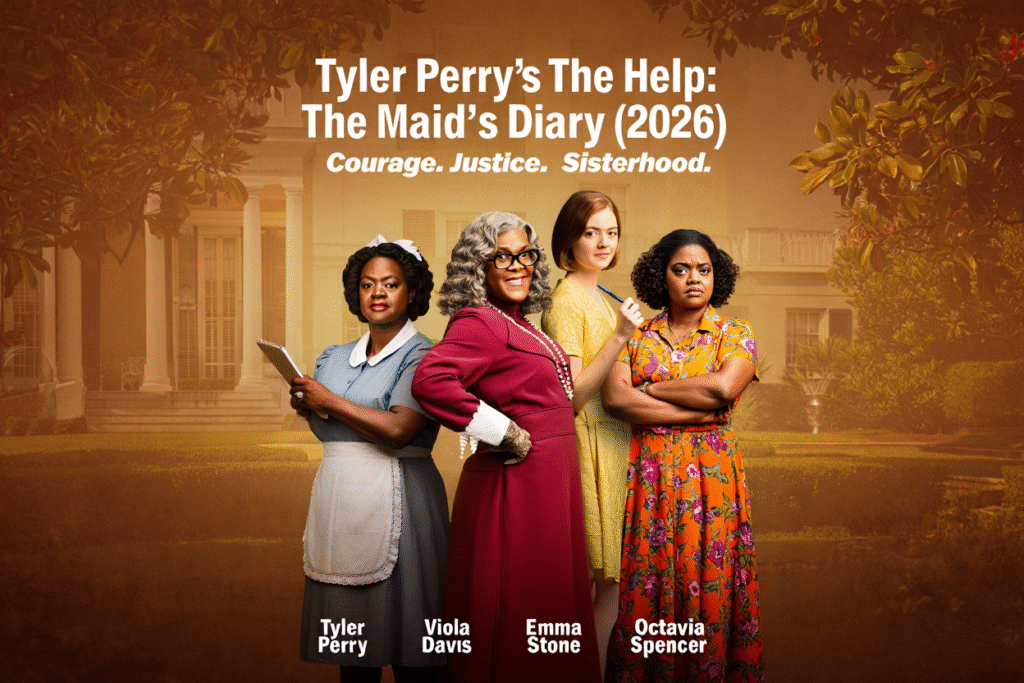

Tyler Perry’s The Help: The Maid’s Diary (2026) dares to revisit a familiar story, but it does so with a bold tonal shift that redefines how pain, courage, and resistance are expressed. This is not merely a reimagining of The Help—it is a fusion of historical drama and Perry’s unmistakable voice, where humor becomes armor and honesty becomes rebellion.

Set once again in the racially segregated South of the 1960s, the film immerses us in a world where silence is enforced and dignity is negotiated daily. Yet from its opening moments, The Maid’s Diary signals that this version will not whisper its truths. It writes them down, speaks them aloud, and dares anyone to look away.

Viola Davis returns as Aibileen with a performance that feels deeper, heavier, and even more resolute than before. Her portrayal carries the weight of years spent loving children she cannot claim and serving families who refuse to see her humanity. Davis communicates strength not through defiance, but through endurance—and that quiet power remains devastating.

Octavia Spencer’s Minny is, as expected, a force of nature. Sharp-tongued, fearless, and emotionally raw, Minny represents the anger that history often tries to soften. Spencer balances humor and fury with precision, reminding us that laughter can be both survival and protest.

Emma Stone’s Skeeter serves as the bridge between worlds, but this time her role feels more reflective. The film subtly questions her privilege and motivations, allowing Skeeter to grow not as a savior, but as a listener—someone learning that telling a story responsibly means knowing when to step back.

The most radical addition, of course, is Madea. Tyler Perry introduces her not as a parody, but as a disruptive truth-teller. Madea’s presence injects humor into unbearable moments, yet beneath every joke is a challenge: why must dignity always be quiet to be considered respectable?

Perry uses Madea as a narrative weapon. She says what others are too afraid to voice, laughs at systems designed to intimidate, and reframes fear as something meant to be confronted, not obeyed. Surprisingly, her inclusion doesn’t trivialize the story—it amplifies its emotional accessibility.

Visually, the film maintains the restrained elegance of a period drama, but emotionally it feels more confrontational. Close-ups linger longer, silences feel heavier, and every shared glance between the maids carries unspoken history. The diary framing device reinforces the idea that these stories were always meant to survive.

The screenplay leans heavily into sisterhood. What emerges is not just a tale of injustice, but one of collective bravery—women choosing truth over safety, voice over invisibility. The bond between Aibileen, Minny, and the other maids becomes the film’s beating heart.

Tonally, The Maid’s Diary walks a risky line between comedy and trauma, but it succeeds by never mocking the pain it portrays. The humor exists to release pressure, not erase suffering. It reminds the audience that joy, too, is a form of resistance.

In the end, Tyler Perry’s The Help: The Maid’s Diary is about ownership—of stories, of voices, of truth. It asks not whether history should be retold, but who gets to tell it, and how loudly. Emotional, provocative, and unexpectedly empowering, this film ensures that the voices once confined to kitchens and back rooms are finally heard—boldly, unapologetically, and in ink that cannot be erased.