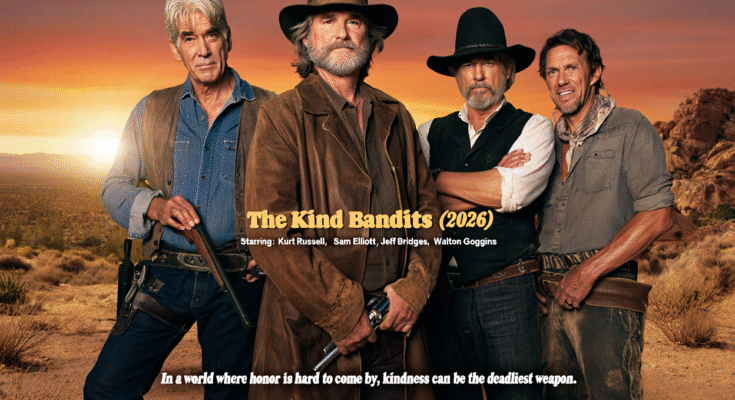

The Kind Bandits (2026) arrives as a quietly devastating Western, one that trades youthful bravado for weathered souls and asks what becomes of men who outlive the violence that once defined them. This is not a film about becoming legends—it’s about surviving long enough to question whether those legends were ever worth the blood spilled to create them.

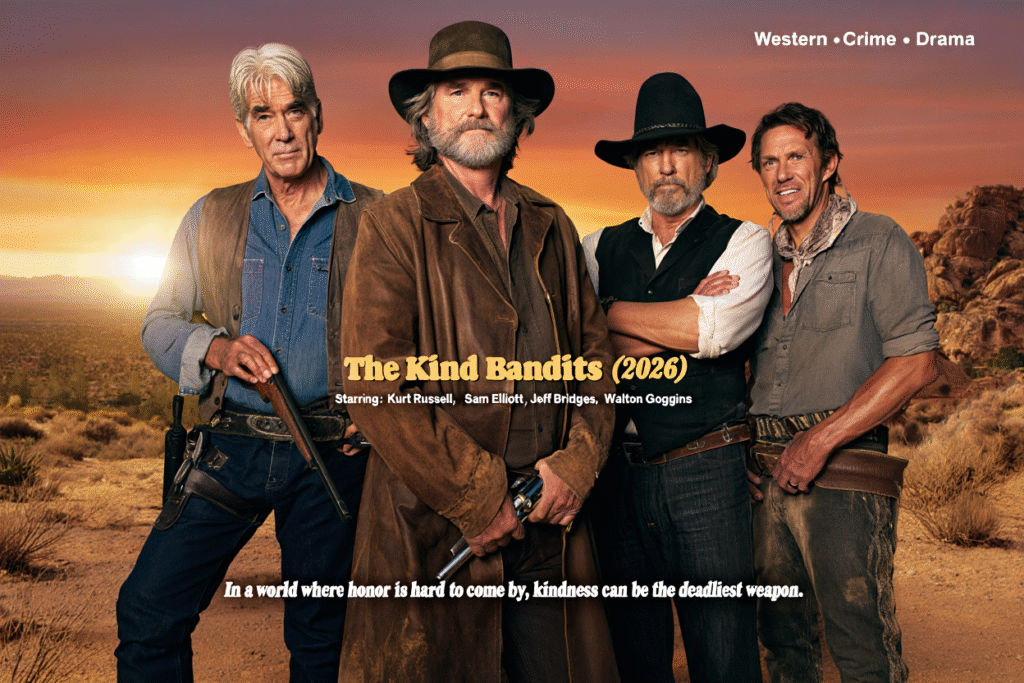

Kurt Russell, Sam Elliott, Jeff Bridges, and Walton Goggins form a quartet that feels less like a cast and more like a reckoning. Each performance carries the weight of years, not just in age but in moral exhaustion. These men don’t ride into towns looking for trouble anymore; trouble follows them, shaped by memories they can’t outrun.

Russell anchors the film with a performance steeped in quiet authority. His character speaks less, but every glance suggests a man who has spent decades choosing survival over virtue—and now wonders if survival alone was enough. There’s a sorrow beneath his restraint that gives the film its emotional backbone.

Sam Elliott brings a haunting dignity, his gravelly presence embodying the old Western code of honor that no longer seems to exist. He plays a man loyal to principles the world has abandoned, clinging to them not because they work, but because letting go would mean admitting everything was for nothing.

Jeff Bridges injects the story with weary introspection. His bandit is thoughtful, ironic, and deeply self-aware, often questioning their path aloud while knowing full well he’ll keep riding it. Bridges makes regret feel lived-in, not performative—a slow ache rather than a dramatic confession.

Walton Goggins is the wildcard, delivering a character whose kindness feels the most dangerous of all. His unpredictability keeps both the audience and the other bandits on edge, blurring the line between redemption and self-deception. You’re never quite sure if he believes in mercy—or simply wants to see if it’s still possible.

The film’s central idea—that kindness can be more lethal than cruelty—is explored with patience and nuance. Small gestures carry enormous weight: a spared enemy, a returned coin, a gun left unfired. In a genre defined by violence, The Kind Bandits understands the radical power of restraint.

Visually, the film is steeped in dust, shadow, and fading light. Wide landscapes emphasize how small these men have become against the passage of time, while intimate close-ups force us to confront every wrinkle, scar, and unspoken regret. The West here is not romantic—it’s honest.

The heist itself is almost secondary, serving as a narrative excuse to push these characters toward moral confrontation. What matters isn’t whether they succeed, but what they choose to do when success demands they become the men they no longer want to be.

The pacing is deliberate, sometimes uncomfortably so, mirroring the slow realization that redemption doesn’t arrive in dramatic moments—it creeps in through doubt, hesitation, and quiet acts of decency. The film trusts its audience to sit with that discomfort.

By the time The Kind Bandits reaches its final moments, it becomes clear this isn’t a story about escaping the past, but about making peace with it. It’s a Western for an older, wiser audience—one that understands that the hardest gun to lay down is the one pointed inward. ⭐