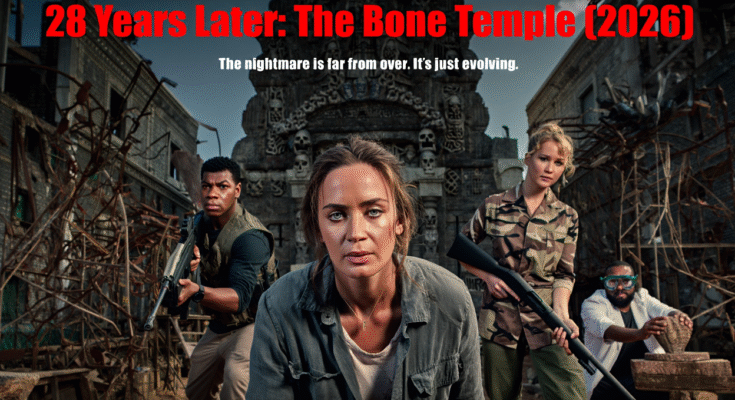

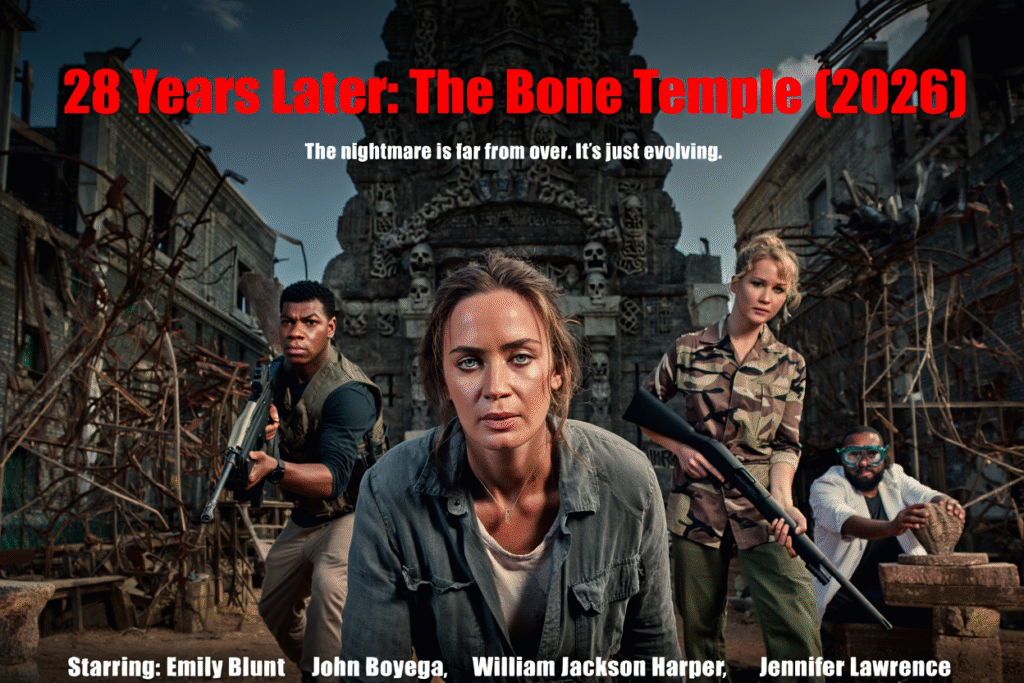

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple (2026) doesn’t just continue the legacy of one of horror’s most devastating franchises—it mutates it into something far more unsettling. Where the original films focused on speed, infection, and collapse, this sequel dares to ask a more terrifying question: what if the end of the world was only the surface of something ancient, patient, and alive?

Emily Blunt’s Sarah has evolved from survivor to reluctant leader, and the film wisely builds its emotional core around that transformation. Blunt plays her with exhaustion etched into every decision, a woman carrying the unbearable weight of rebuilding a world that may not want to be rebuilt. Her performance grounds the film’s escalating madness in human consequence.

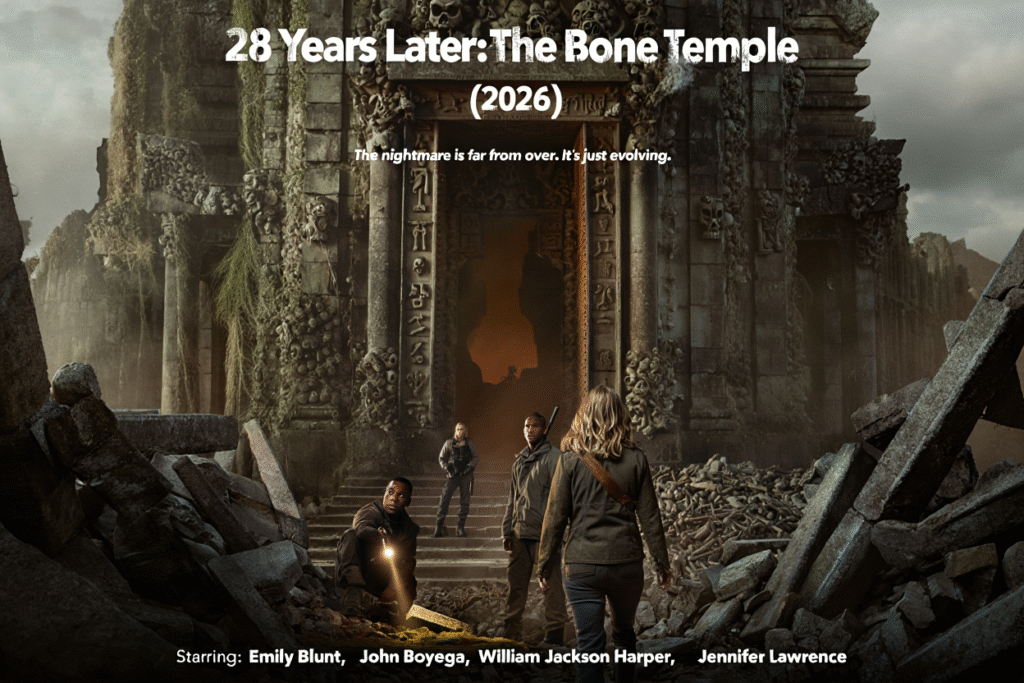

The discovery of the Bone Temple marks a tonal shift for the franchise. This is no longer just post-apocalyptic horror—it’s archaeological dread. The temple, constructed of human remains and ritualistic design, feels timeless and wrong, as if it has been waiting for civilization to collapse before revealing itself. The virus, once a scientific nightmare, now feels like a symptom rather than the disease.

John Boyega’s Marcus provides the emotional counterbalance to Sarah’s burdened resolve. His loyalty is unwavering, but his growing realization that humanity may have misunderstood the outbreak adds layers of dread. Boyega brings quiet intensity to the role, making Marcus feel like the audience’s moral compass in a world losing its bearings.

William Jackson Harper steals scenes as the obsessed scientist whose intellect begins to blur into reverence. His fascination with the temple’s occult origins is deeply unsettling, not because he’s villainous, but because he represents humanity’s oldest flaw: curiosity without restraint. Harper plays him with chilling calm, making his descent all the more disturbing.

Jennifer Lawrence’s Eva injects the film with raw physical urgency. As a hardened soldier, she embodies the belief that violence and discipline are the only remaining languages of survival. Yet even she begins to crack when the enemy stops behaving like something that can be shot or outrun. Lawrence’s performance is fierce, feral, and increasingly desperate.

Visually, The Bone Temple is oppressive in the best way. The cinematography leans into shadows, flickering torchlight, and claustrophobic framing, making every descent into the temple feel like a journey into the earth’s memory. Bones aren’t just scenery—they’re architecture, history, and warning.

The horror here is less about jump scares and more about revelation. Each layer of the temple peels back humanity’s arrogance, suggesting that the outbreak may have awakened something that predates modern civilization. The infected no longer feel like the ultimate threat—they feel like guardians, or consequences.

What makes the film especially effective is its restraint. It never fully explains the temple’s origin, allowing myth, science, and superstition to collide uncomfortably. This ambiguity lingers, haunting the viewer long after the credits roll, much like the best horror always does.

The pacing is deliberate, sometimes punishingly slow, but intentionally so. The film wants you to feel the weight of time—28 years of decay, denial, and buried truths. When violence erupts, it’s sudden, brutal, and deeply earned.

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is a bold evolution of the franchise, trading pure infection horror for existential dread. It suggests that humanity didn’t just lose control of the world—we were never its masters to begin with. This isn’t just the next chapter of the nightmare. It’s the realization that the nightmare was always older than us.