In the aftermath of Michael Myers’ apparent demise, this new chapter doesn’t rush to replace the monster — it questions whether he was ever the true source of evil at all. Haddonfield exhales, believing the nightmare has finally ended, but the film wisely understands that horror doesn’t disappear just because its most recognizable face is gone. Sometimes, it simply changes shape.

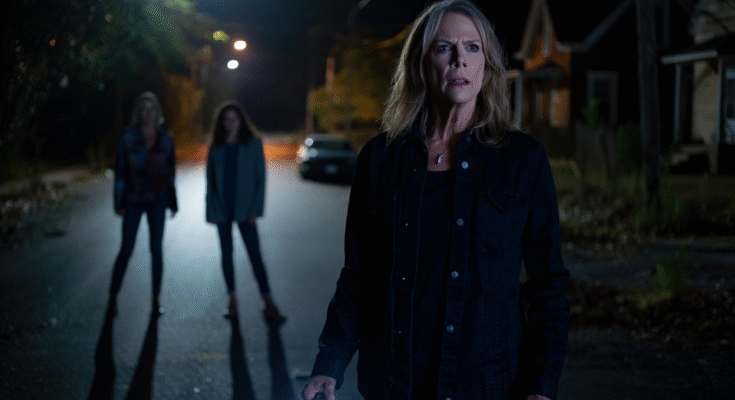

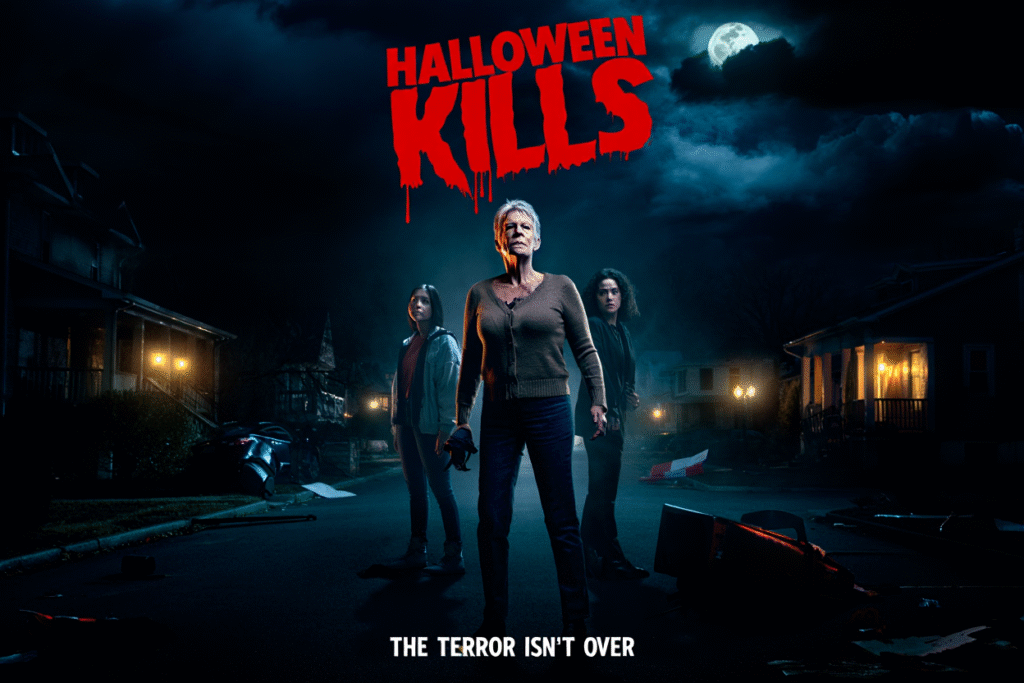

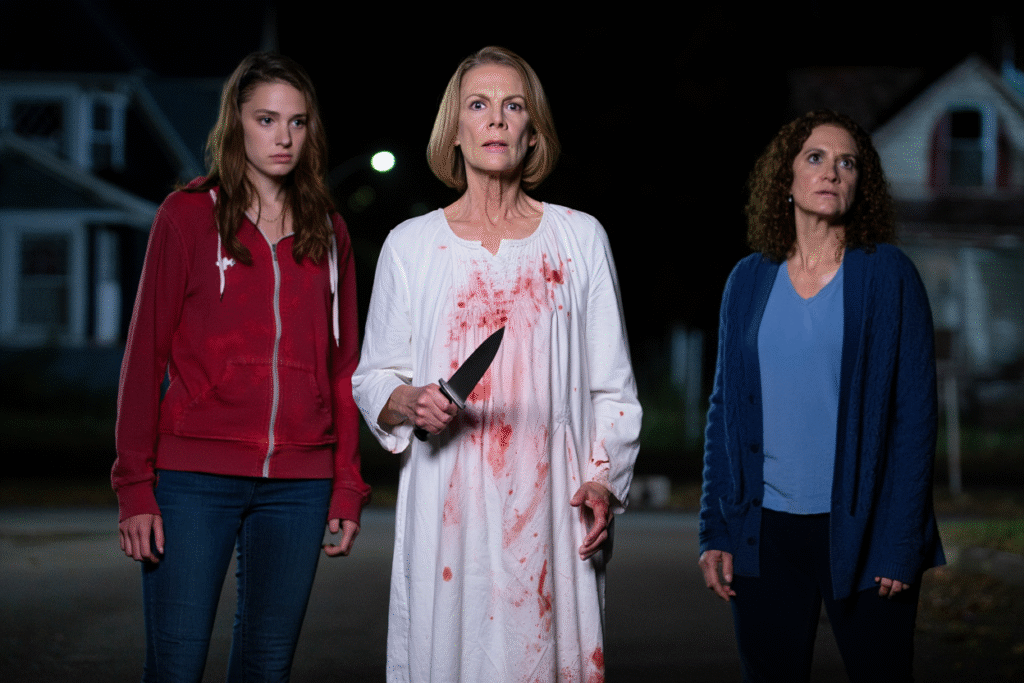

Jamie Lee Curtis returns as Laurie Strode with a performance steeped in exhaustion rather than rage. Laurie is no longer just a survivor or a warrior — she is a woman burdened by the realization that closure may be a lie. Curtis plays her with a quiet intensity, conveying the unsettling truth that surviving trauma doesn’t guarantee freedom from it.

What makes this story compelling is its refusal to let the town heal easily. Haddonfield itself feels wounded, almost resentful, as if it has grown dependent on fear. The absence of Michael creates a vacuum, and something far more insidious begins to fill it — not a copycat, but a consequence.

Allyson, portrayed by Andi Matichak, steps further into the emotional center of the narrative. Her character embodies a generation raised in the shadow of terror, struggling to define herself without the myth of Michael Myers shaping her identity. Her arc is less about fighting back and more about resisting becoming what the town expects her to be.

Judy Greer’s Karen brings a different energy — pragmatic, guarded, and increasingly suspicious. She senses that the horror stalking them isn’t random. As secrets begin to surface, her fear transforms into something sharper: the realization that evil may have been cultivated, not born.

The film’s greatest strength lies in its thematic ambition. Rather than focusing solely on body counts, it interrogates legacy — how violence echoes, how fear becomes institutionalized, and how communities sometimes need monsters to justify their own darkness. The question of who “orchestrated” the terror is less about identity and more about responsibility.

Visually, the film leans into restraint. Shadows linger longer than necessary. Silence becomes oppressive. Violence, when it arrives, feels abrupt and cruel rather than theatrical. This approach reinforces the idea that the new terror doesn’t announce itself — it infiltrates.

The new entity haunting Haddonfield is deliberately elusive. It doesn’t crave spectacle or legend. It thrives on confusion, manipulation, and psychological erosion. This makes the horror deeply unsettling, as the characters — and the audience — are denied the comfort of a familiar face to fear.

As the town descends into paranoia, the line between victim and accomplice blurs. Old decisions are reevaluated, alliances fracture, and survival becomes less about escaping the dark and more about confronting uncomfortable truths. The film suggests that denial may be more dangerous than any blade.

Laurie’s journey reaches a powerful emotional crossroads. She begins to understand that defeating Michael was never the endgame — breaking the cycle is. And cycles, the film argues, don’t end with violence alone. They end with reckoning.

By its final moments, the story leaves a chilling impression: evil doesn’t need immortality to endure. It only needs permission. This chapter doesn’t try to outdo Michael Myers — it dismantles the myth around him, revealing a far more terrifying possibility.

In the end, this is not just a continuation of a legend — it’s a reflection on what happens when fear becomes tradition. And when the credits roll, one truth lingers longer than any scream: the terror was never just coming for Haddonfield. It was always coming for what lived inside it.