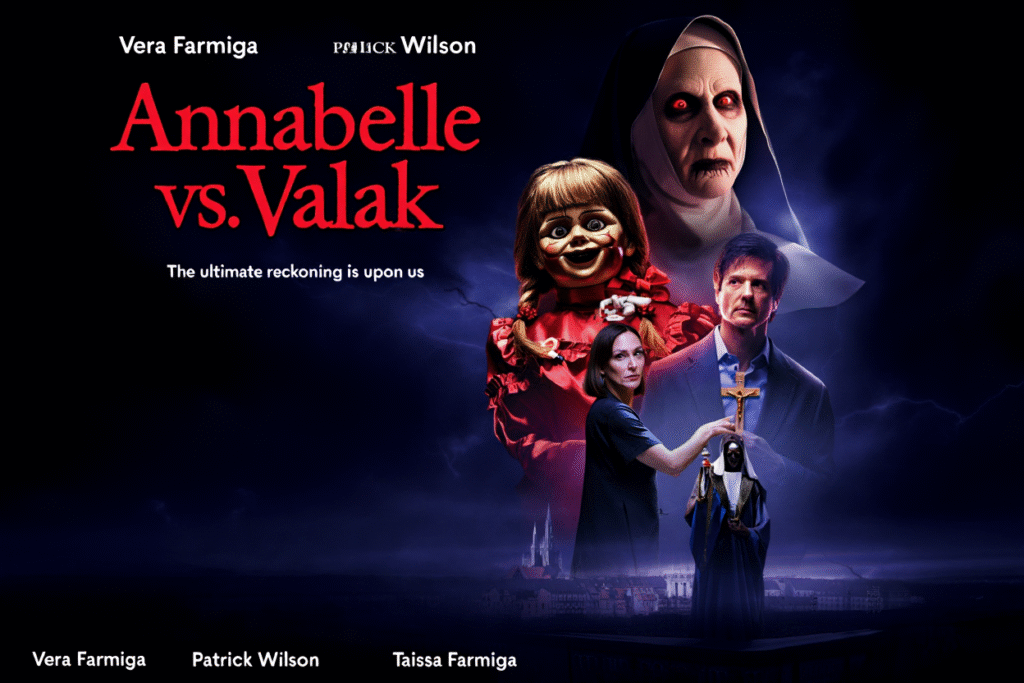

Annabelle vs. Valak is positioned as the ultimate convergence film of The Conjuring universe, and it understands the weight of that promise. Rather than functioning as a loud crossover spectacle, the film leans into dread, theology, and inevitability — treating this clash not as a gimmick, but as a spiritual war that was always destined to happen.

Vera Farmiga and Patrick Wilson return as Ed and Lorraine Warren with a gravity that anchors the film from its opening frames. There’s a sense of exhaustion in their performances, as though every case they’ve faced has led them here. Lorraine, in particular, feels haunted before the terror even begins — her visions fractured, her faith tested not by fear, but by the possibility that evil has learned how to wait.

The film’s central concept — Valak attempting to weaponize Annabelle as a conduit rather than a rival — is a smart subversion. Evil doesn’t fight for dominance out of pride here; it strategizes. Valak is portrayed less as a jump-scare machine and more as an ancient intelligence, cold and calculating, while Annabelle remains raw, chaotic, and cruel. Their “conflict” is less physical and more metaphysical, unfolding through possession, rituals, and corrupted visions.

Taissa Farmiga’s presence adds a crucial emotional layer, serving as both connective tissue to the franchise and a symbol of what’s at stake. Her character becomes a spiritual fault line — someone both demons seek to influence, not because of power, but because of belief. The film repeatedly asks whether faith is armor or invitation.

Visually, Annabelle vs. Valak is one of the darkest entries in the universe, both literally and thematically. Candlelit exorcisms, collapsing churches, and warped reflections dominate the cinematography. Mirrors and glass recur as motifs, reinforcing the idea that evil is no longer trying to hide — it wants to be seen.

The horror is deliberate rather than relentless. Long stretches of silence, whispered Latin prayers, and distorted religious imagery create a suffocating atmosphere. When violence erupts, it feels earned and shocking, emphasizing consequence over spectacle. This restraint allows the film’s psychological horror to linger far longer than its scares.

Lorraine’s arc is the emotional spine of the story. Valak doesn’t just threaten her life — it attacks her memory, her past victories, and the idea that she ever truly saved anyone. The film’s most disturbing moments aren’t demonic appearances, but scenes where Lorraine questions whether every soul she “rescued” was merely postponed.

Patrick Wilson’s Ed is portrayed as steadfast but fragile, a man whose belief is no longer unshakable, yet refuses to collapse. His role here is less warrior and more witness — someone watching the cost of faith accumulate in real time.

The final act avoids a traditional “winner.” Instead, it delivers a reckoning. The confrontation between Annabelle and Valak feels less like a battle and more like a revelation — exposing that evil doesn’t destroy itself through conflict, but through exposure. What’s left behind is not victory, but survival.

By the time the credits roll, Annabelle vs. Valak feels like both an ending and a warning. It suggests that the true horror isn’t demons clashing, but the realization that evil evolves — learning patience, strategy, and restraint. This isn’t just another chapter in The Conjuring saga. It’s the moment the universe looks back at itself and asks whether it was ever truly in control.