1887: The First Winter strips the Western genre down to its rawest elements: land, blood, cold, and loyalty. This is not a story about expansion or triumph, but about endurance — the kind that slowly erodes the soul before it hardens it. From its opening frames, the film announces itself as a battle not just against nature, but against despair itself.

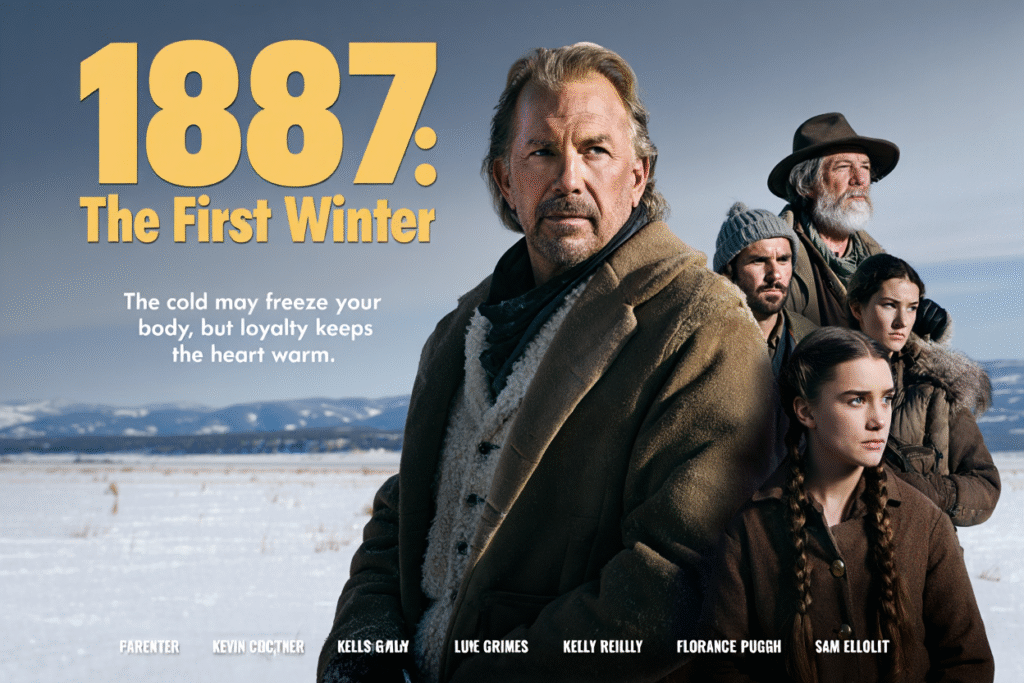

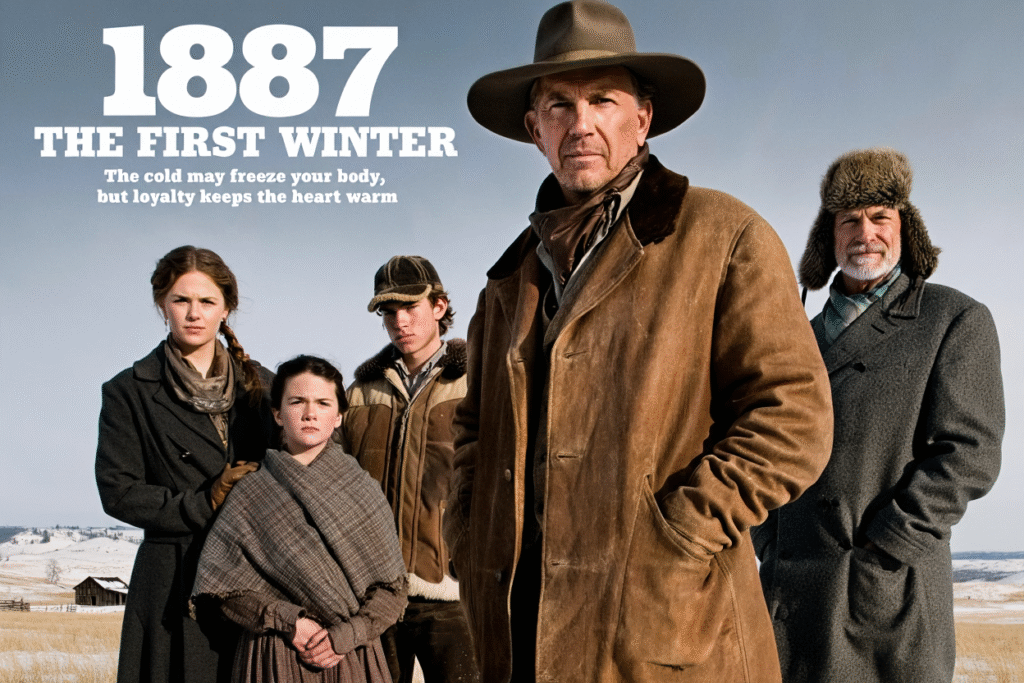

Kevin Costner’s James Dutton is a man forged by responsibility, and Costner plays him with weary authority. This is not the romantic pioneer of legend, but a leader haunted by every decision he makes. Each choice — who eats, who works, who risks death — carries weight, and the film never lets us forget the cost of survival when resources vanish and hope freezes over.

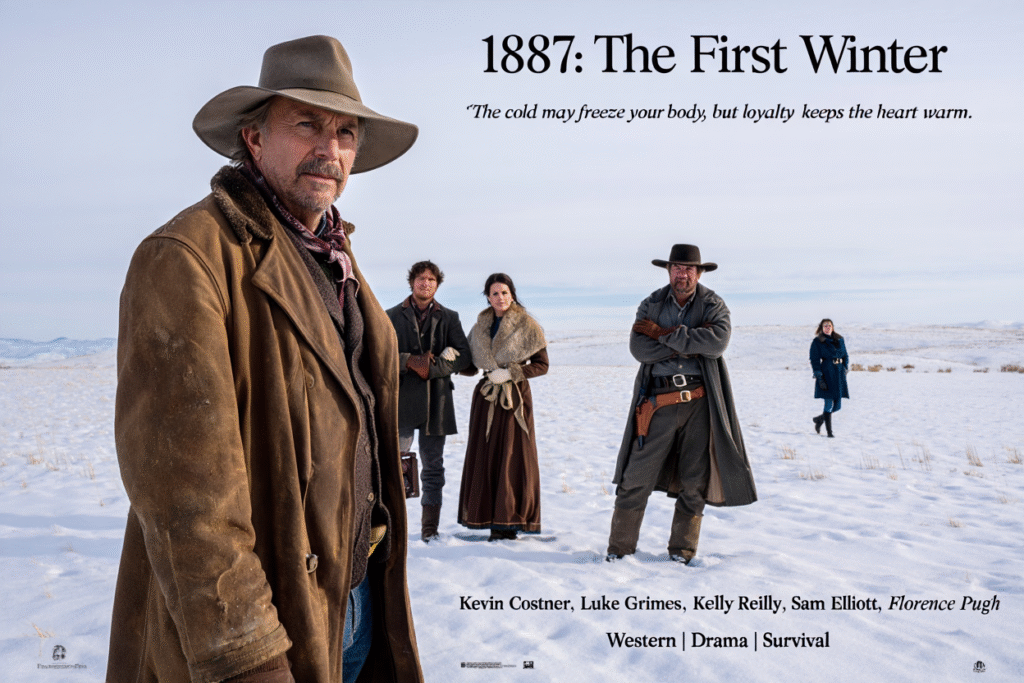

The winter itself is the film’s most merciless antagonist. Snow doesn’t simply fall; it entombs. Wind howls like an accusation, and silence becomes suffocating. Director and cinematography lean into wide, unforgiving landscapes, making human figures look painfully small against a world that does not care whether they live or die.

Kelly Reilly delivers one of the film’s most compelling performances as James’s wife — fierce, pragmatic, and emotionally unbreakable. She is the emotional backbone of the family, refusing to allow fear to paralyze her. Where James hesitates, she steadies him; where others collapse, she adapts. Her strength feels earned, not symbolic.

Luke Grimes brings quiet intensity as the son caught between inherited duty and personal doubt. His arc is subtle but powerful — a young man learning that legacy is not something you inherit, but something you survive long enough to protect. His silence often speaks louder than dialogue, especially in moments of moral conflict.

Sam Elliott’s hardened neighbor is pure frontier wisdom — a man shaped by loss and stripped of illusions. Elliott’s gravelly presence adds gravity to every scene he’s in, serving as both warning and mirror to James Dutton: survive long enough, and survival itself will change you.

Florence Pugh is the film’s revelation. Her character is not framed as a savior, but as a strategist — resilient, observant, and emotionally grounded. She understands that survival is not about strength alone, but about knowing when to bend, when to endure, and when to act. Her presence injects urgency and intelligence into the narrative.

What sets 1887: The First Winter apart from typical Westerns is its refusal to glorify suffering. Death is not heroic here; it is quiet, sudden, and deeply unfair. Hunger isn’t dramatic — it is slow, humiliating, and relentless. The film asks the audience to sit with discomfort rather than escape it.

Themes of loyalty pulse through every decision. Family is not portrayed as unconditional comfort, but as obligation — sometimes unbearable, sometimes lifesaving. The question the film keeps asking is simple yet brutal: how much are you willing to sacrifice to protect what you call yours?

The pacing is deliberate, mirroring the slow grind of winter itself. Some scenes linger longer than expected, but this patience is intentional. Survival doesn’t move quickly; it drags. And the film understands that rushing would betray its truth.

By the time the snow begins to thaw, 1887: The First Winter leaves us changed. It is a story about the cost of legacy, the violence of nature, and the quiet heroism of those who endure without guarantee of reward. In the end, the film doesn’t celebrate survival — it respects it.