The Haunting of Maplewood Manor understands its assignment immediately: this is not a horror film pretending to be funny, nor a comedy awkwardly borrowing ghosts. It is a deliberate horror-comedy that treats both genres with respect. The film balances genuine supernatural tension with character-driven humor, proving that scares land harder when laughter has already lowered your guard.

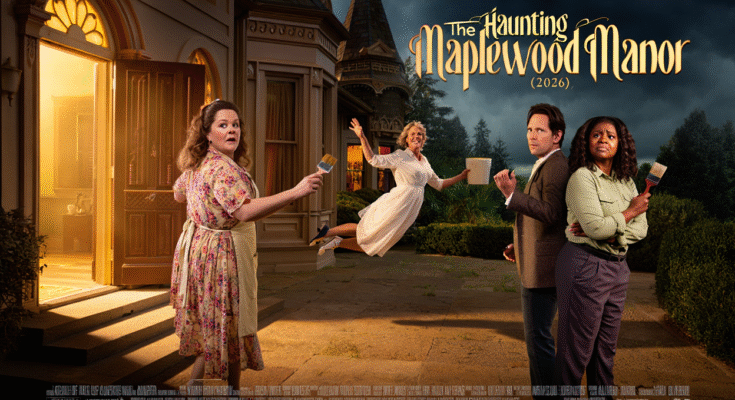

Melissa McCarthy anchors the film with one of her most controlled comedic performances in years. Linda Harper isn’t a cartoon; she’s a financially desperate optimist clinging to a dream that is literally slamming doors in her face. McCarthy’s humor comes from exhaustion, denial, and quiet disbelief rather than volume, which makes the escalating chaos funnier — and occasionally sadder — than expected.

Jamie Lee Curtis is predictably excellent as Dr. Eleanor Graves, an “emotionally unstable house” specialist who treats hauntings like unresolved therapy sessions. Curtis plays the role with razor-sharp dryness, grounding the supernatural mythology while stealing scenes with deadpan delivery. Her presence lends credibility to the horror elements, reminding audiences that she remains one of the genre’s most reliable figures.

Paul Rudd’s Mark Bennett functions as the film’s skepticism barometer. Initially charming and dismissive, his gradual breakdown — especially during the wine cellar sequence — becomes one of the movie’s comedic highlights. Rudd excels at portraying rational confidence dissolving into reluctant belief, and the film smartly allows him to be funny without undermining the stakes.

Octavia Spencer is the film’s quiet MVP. Denise Carter treats hauntings like customer service issues, and Spencer’s restrained reactions provide the perfect counterbalance to McCarthy’s spiraling energy. Her grounded performance gives the film emotional stability, especially when the story shifts from slapstick chaos to genuine danger.

Visually, the film leans into classic haunted-house aesthetics without overdoing CGI. Candlelit hallways, creaking staircases, and shadowy corners are used sparingly but effectively. The ghosts themselves are eerie rather than grotesque — translucent, elegant, and unsettling — reinforcing the idea that unresolved grief can be more disturbing than outright monstrosity.

The 1890s scandal at the heart of the haunting is surprisingly well-developed. Instead of a throwaway backstory, the film slowly reveals betrayal, repression, and social cruelty that mirror modern emotional wounds. The ghosts aren’t evil — they’re stuck, dramatic, and deeply petty, which makes their presence oddly human.

Tonally, the film walks a difficult line and mostly succeeds. The first half leans heavily into comedy, while the third act tightens into real suspense. When the hauntings turn dangerous, the humor doesn’t disappear — it simply becomes more nervous, more desperate, and more revealing of character.

The improvised exorcism sequence is pure chaos in the best way: mispronounced Latin, conflicting belief systems, and escalating supernatural backlash collide into one of the film’s most memorable set pieces. It’s funny, stressful, and surprisingly emotional — a reminder that closure isn’t neat, even in death.

The Haunting of Maplewood Manor may not redefine horror-comedy, but it executes the genre with confidence, warmth, and sharp timing. It understands that ghosts don’t just haunt spaces — they haunt unresolved emotions. And sometimes, the only way to move on is to confront the past… even if it criticizes your wallpaper first.