The Stillborn Light is not a horror film that startles—it erodes. It seeps under the skin with the quiet persistence of grief itself, turning domestic stillness into something unbearable. From its opening frames, the film makes a devastating promise: this story will not comfort you, and it will not let you look away.

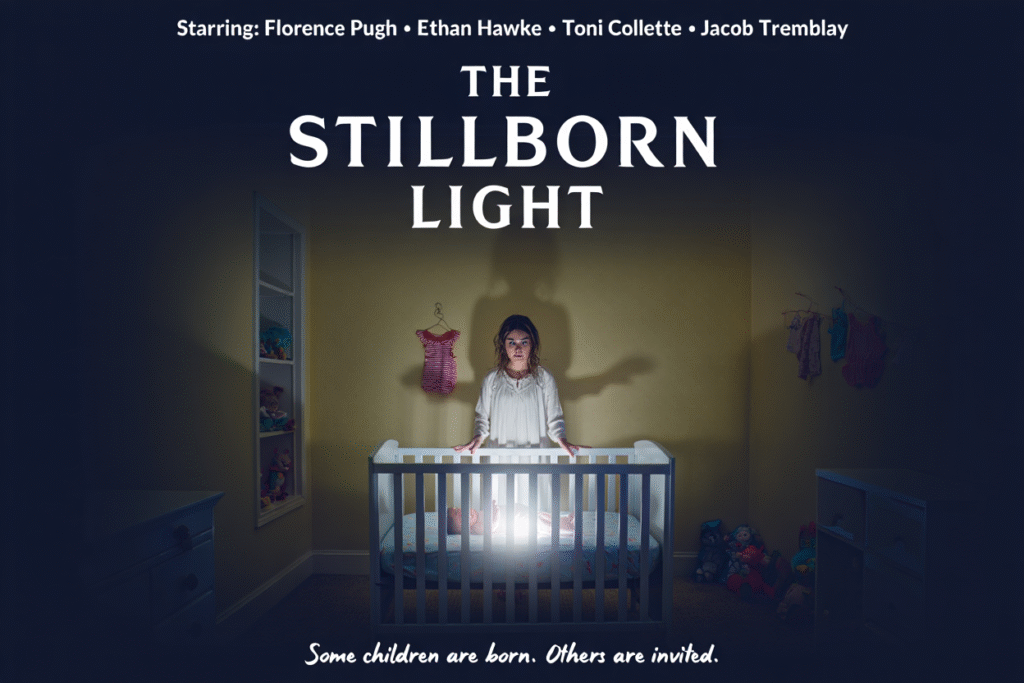

Florence Pugh delivers one of the most harrowing performances of her career as Claire Mercer, a woman trapped in the aftermath of stillbirth where time has stopped but pain has not. Pugh plays grief not as melodrama, but as paralysis—her movements slow, her voice hollowed, her eyes constantly searching for something she knows is gone. The untouched nursery becomes less a room than a wound, and every silent moment feels loaded with unspoken guilt.

Ethan Hawke’s Daniel is equally compelling in restraint. Rather than portraying denial as cruelty, Hawke frames it as desperation. His insistence on rational explanations—faulty electronics, shared hallucinations, stress responses—feels like a man clinging to structure because chaos has already taken too much. The film’s emotional core lies in the widening chasm between them: one parent reaching toward the impossible, the other barricading himself inside reality.

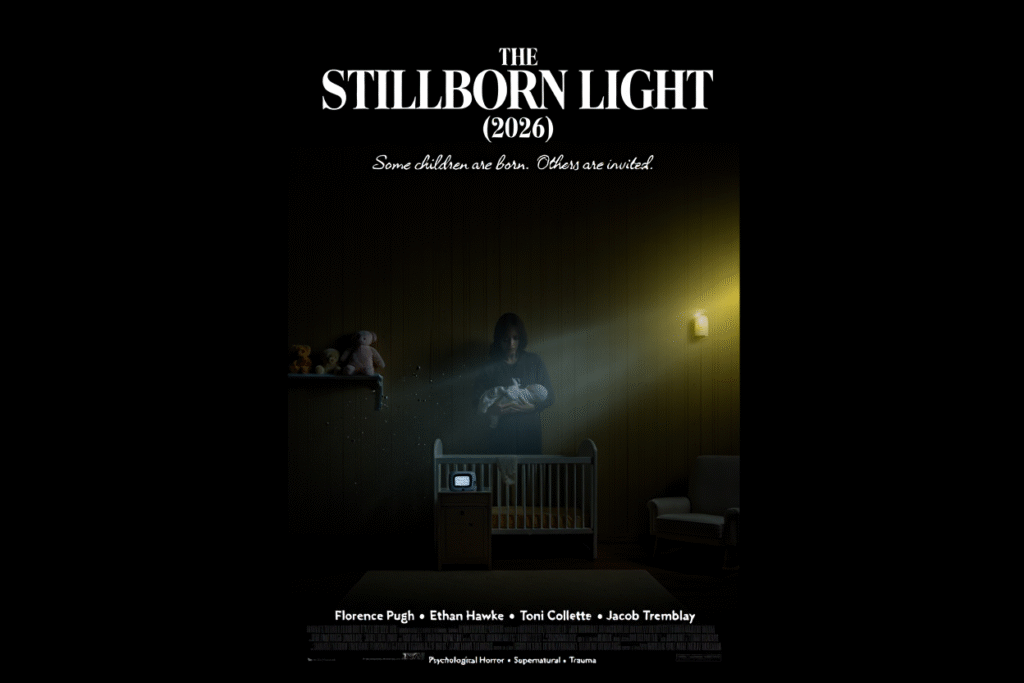

The baby monitor is the film’s most devastating device. Its use is minimal, precise, and cruel. Breathing. Static. A lullaby at 2:12 AM. These sounds are never exaggerated or weaponized with jump scares; instead, they feel intimate, invasive—like overhearing something you were never meant to hear. The horror doesn’t ask what is happening. It asks why you want it to be happening.

Toni Collette’s Dr. Halpern provides no easy authority or safety net. Her unease grows subtly, almost imperceptibly, as Claire’s experiences stop fitting within therapeutic language. Collette plays her not as a skeptic or believer, but as someone slowly realizing that grief may not be metaphorical in this case—it may be literal bait.

Jacob Tremblay’s brief but chilling role is one of the film’s most unsettling elements. His quiet certainty—“the baby walks at night”—is delivered without menace, without drama. That innocence makes it unbearable. The film understands that children don’t invent horror; they recognize it.

What elevates The Stillborn Light beyond conventional supernatural horror is its refusal to equate the entity with the lost child. This is not a story about resurrection or haunted innocence. The presence is something opportunistic, ancient, and parasitic—drawn not by death, but by love left with nowhere to go. The idea that grief itself can function as an invitation is both original and profoundly disturbing.

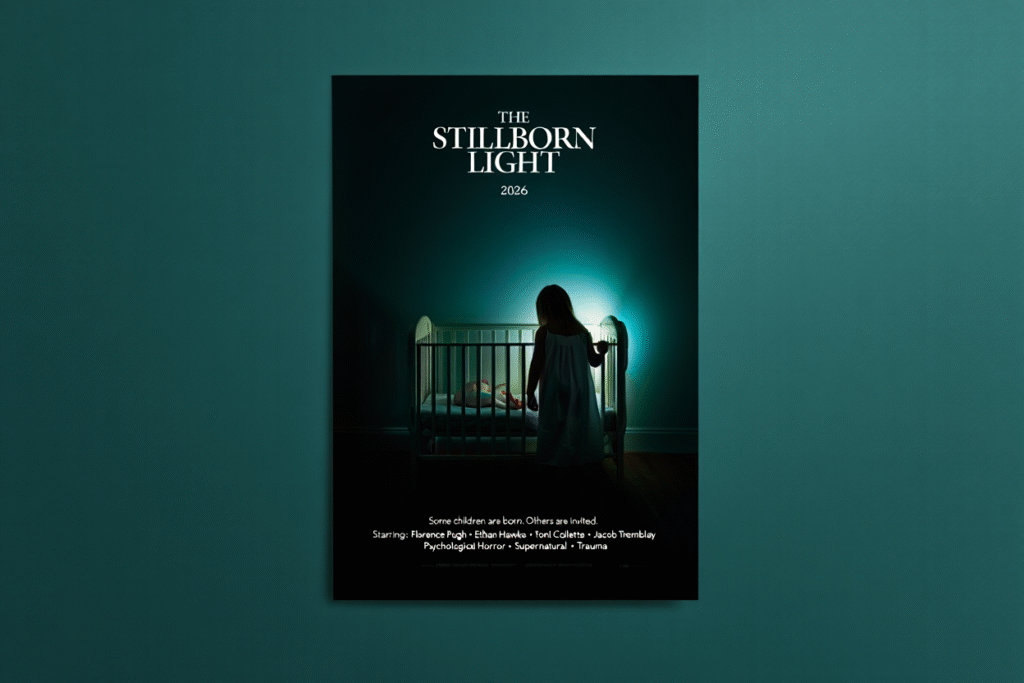

Visually, the film is suffocating in its restraint. Cold color palettes, static framing, and negative space dominate the house. The nursery light—soft, warm, wrong—becomes a symbol of unresolved longing. When shadows move, they do so subtly, often at the edges of perception, forcing the viewer to question whether they saw anything at all.

The final confrontation in the nursery is not loud or cathartic. It is quiet, intimate, and devastating. The silhouette cradling “nothing… and everything” is one of the most haunting images in recent horror cinema, not because of what it shows, but because of what it represents: grief given form, fed by acknowledgment.

The Stillborn Light is not entertainment in the traditional sense. It is an endurance test—one that treats trauma with respect and horror with restraint. There are no villains to defeat, no curses to lift, no closure neatly offered. Only a question that lingers long after the credits fade:

If love refuses to let go…

what answers back?